Hello Visitor! Log In

Overcoming the Global Trilemma: New Monetary Politics in the Anthropocene: Dani Rodrik Revised

ARTICLE | October 12, 2019 | BY Stefan Brunnhuber

Author(s)

Stefan Brunnhuber

Abstract

This paper will review the concept of the “open economic trilemma” between national sovereignty, global integration and democratic politics. It will introduce, as a possible solution, the concept of a parallel dual currency system operating through new monetary channels using distributive ledger technology. Although not apparent at first glance, this additional system could provide a Pareto-superior optimum by integrating spillovers and negative externalities and by fostering political efficacy on a national level. Monetary autonomy, national sovereignty and further global integration could thus become possible. In short, the existing global currency system leaves global economic integration in a suboptimal equilibrium. The current hype surrounding cryptocurrencies provides a preliminary rationale for a dual currency system. Designed in the right manner, a dual currency system could provide the necessary change towards greater wealth while leading to a more sustainable planet.

1. Introduction

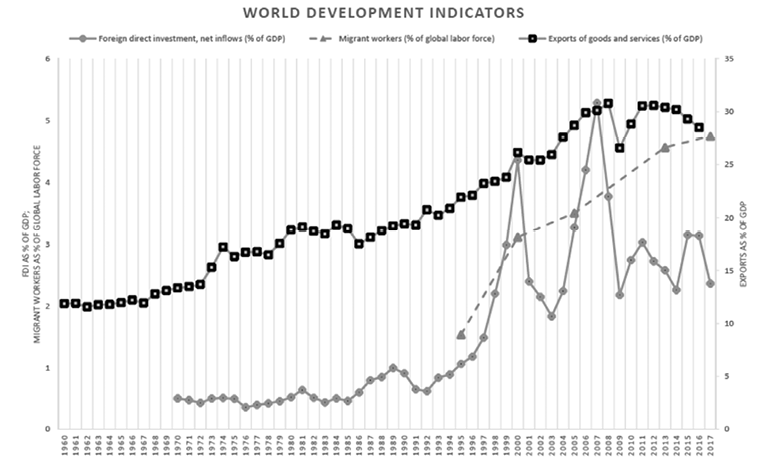

Global economic integration is considered to be a measure of globalization, where capital, goods and services, as well as labor forces operating outside domestic borders, offer additional wealth, jobs, and increased efficiency and productivity for an even larger population globally. However, the figures below show that the world community is far from being totally integrated. In fact, foreign direct investments (FDI) represent some 2% of global GDP,* migrant workers account for only 150 million of the 3.5 billion global labor force,1 representing less than 5% (ILO estimates 2017),† and even international trade accounts for less than 30% of GDP.‡ So despite globalization, most capital, most trading of goods and services, and most human labor remain primarily domestic, taking place within national borders.

Despite economic integration’s positive effects on alleviating poverty, increasing longevity and boosting economic wealth, there are also negative consequences that affect domestic politics and economics on a global scale. Nations and their citizens are more likely than ever to be affected by asymmetric shocks in the form of financial crises (banking, currency, and sovereign debt crises), armed conflict (failed states, asymmetric wars), demographic changes (birth rate, migration, aging), ecological challenges (global warming, loss of biodiversity, rare earths) or social risks (pandemics, poverty, unemployment). None of these adverse effects can be attributed to one specific national policy. In fact, even if a nation’s domestic policy has done everything ‘right’, it can still be disproportionately affected. These forms of integration, also referred to as global interconnectedness, characterize the Age of the Anthropocene, to use a term popularized by Paul Crutzen.2 The Anthropocene requires a new form of global governance in the name of humankind. Examples of such endeavors include the UN Declaration of Human Rights, the COP21 treaty to protect the planet, and the World Trade Organization trading treaty, to name a few.

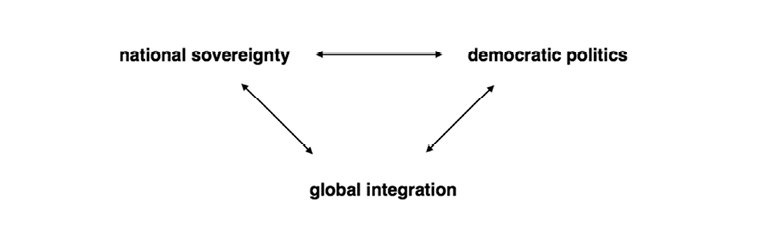

2. The Global Trilemma

The “open economy trilemma” introduced by Oxelheim (1990) and Obstfeld & Taylor (1998)3 states that countries cannot simultaneously maintain independent monetary policies, fixed exchange rates, and an open capital account. To use extreme cases as an example: if a government chooses free capital flow (with no tariffs and controls) and monetary independence (mainly raising or lowering interest rates as they choose), it will have to abandon fixed exchange rates and will end up with floating ones. If a government instead opts for fixed exchange rates and an autonomous monetary policy, it will end up with a Bretton Woods scenario, with no or reduced capital mobility. And if a government wants fixed exchange rates and free capital flow, it will have to give up monetary autonomy, as experienced in the age of the gold standard. This trilemma was further built upon in Dani Rodrik’s seminal papers, where nation-states, democratic politics and the deepening of global economic integration lead to an inescapable “global paradox” (2000, 2010).4 In this reading, if the government chooses nation-state sovereignty and democratic politics, it has to renounce further global integration, ending up with some sort of Bretton Woods agreement. If the government embraces deepening global integration and democratic politics, it will end up with increased global federalism and less national sovereignty. And if a government chooses to strengthen global integration and nation-states, it will end up with a golden straitjacket and limited leverage for democratic voting: it is possible to have two—any two—but never all three.

Focusing on further global integration (globalization) would require us to eliminate the differences in transaction costs that sovereign states impose on economic activities (sovereign risks, regulatory discontinuity or costs for the supervision of the domestic financial intermediaries). This would in consequence reduce the impact of democratic voting and national sovereignty. How far should this economic integration, which is far from complete, continue in order to provide the greatest benefit for humankind and the planet? Can we further increase economic integration globally, while simultaneously ensuring sovereign nation-states, sovereign monetary policies and a democratic mandate? What are the necessary monetary tools to provide a realistic exit out of the trilemma described above? In the following, we will attempt to answer these questions and demonstrate one way out of this trilemma, where pegged exchange rates, an independent monetary policy and free capital flow are possible within the context of democracy and deepening global economic integration, while at the same time maintaining the sovereignty of nation-states.

3. The Unquestioned Assumption

The approaches of Oxelheim (1990),5 Obstfeld & Taylor (1998) and Rodrik (2000, 2010) describe an inescapable trilemma. Humankind is trapped in this trilemma with no way out. However, the trilemma, irrespective of the form it takes and the components relating to each other, is based on an unquestioned assumption: the globally operating monetary system is taken for granted. It is this global monetary monoculture, through which all capital flows and all goods and services are traded, that places a golden straitjacket around national sovereignty and monetary policy. In addition, it is this monetary monoculture that limits democratic voting and diminishes the full potential of the future wealth of nations. Despite the fact that over 150 currencies are available globally, they all follow the same design and use the same monetary channels to provide the liquidity required for the economy.

“Complementary currencies will make the overall system more stable and resilient, thereby steering our society towards a more sustainable world and providing better tools to solve real problems.”

However, if we had an additional monetary system created in a different way and running in parallel to the existing system using different monetary channels, we would be able to overcome the trilemma described above.6 There is in fact preliminary evidence for three such parallel currency systems operating already, which can be further distinguished as a top down and a more bottom up approach. The goals are that these complementary currencies will make the overall system more stable and resilient, thereby steering our society towards a more sustainable world and providing better tools to solve real problems. From a top down perspective there are over a dozen central banks currently experimenting with so-called CBDCs (Central Bank Digital currencies).7 The purpose is to expand the base money and to better provide control and regulation over the overall monetary and fiscal system. CBDCs are running in digital form only, providing an additional lender of last resort. In this setting, money remains a public good.

From a bottom up perspective there are two major trends: On the one hand, so-called community currencies and on the other, cryptocurrencies. Community Currencies8 do not necessarily replicate the ‘general purpose’ of conventional money (medium of exchange, store of value etc.), but often emphasize a ‘special purpose’ like targeting specific social or environmental projects or local business providing additional liquidity to a sector or region, where there is a shortage in supply. Empirically there are over 3400 such local and regional projects in 23 countries across six continents using different forms of such community currencies. Despite their diversity, they can be grouped into four categories, including service credits (Time dollars), mutual exchange schema (LETS), local or regional currency schemas (Bristol Pound, RegioMoney) and Barter (Trueque). The capitalization of community currencies is low, their macroeconomic impact often irrelevant, but over 50% of those activities are growing and some of them have over 75 years of history. They simply demonstrate on a case to case evidence over decades, in thousands of real time field experiments all over the world that parallel currencies are working and needed.9

The second bottom up approach is cryptocurrencies, currently about 2300 in use.10 Ethereum, Bitcoin, Ripple, Cardano, Skycoin, Libra are such examples, which exclusively run in electronic form using blockchain technology, issued by private initiatives (private mining), mainly following an underlying speculative and investment purpose. They are highly capitalized (2019: 350 Bill USD), highly volatile and they consider money as a private good, favoring denationalizing the money domain. In most cases, they have a so-called built-in smart social contract, a digital algorithm that permits or prevents the additional money to be used for a specific set of transactions. The following table provides a general overview:

Table 1: Parallel Currencies: Empirical Evidence for Additional Targeted Liquidity to solve Real Time Problems

|

Parallel Currencies |

Characteristics |

Purpose |

|

Central Bank Digital Currencies ( >10 experimental) |

extended base money non-defaultable loan public interest |

Control Regulation Steering |

|

Cryptocurrencies (> 2300):Ripple, Ethereum, Skyledger, Libra. |

Denationalization of money High capitalization (2019: 350 Bill USD), smart social contract |

Investment Speculation Commercial |

|

Community Currencies (>3400): Time Dollars (50%) LETS (41%), Barter (1,5%) Regio Money (7%) |

Low capitalization case to case evidence |

Social capital consumptive or local business purposes |

Parallel currencies, once they achieve an adequate volume, can operate as a rescue boat. However properly installed, they have the potential to act as a constant optional medium of exchange or storage of value, not only in case of a monetary crunch or a buffer in case of a crisis or transition phase, but as a safety net for the societal transition in general, becoming an accustomed and ‘normal‘ tool for transactions. And all three approaches can be interpreted as a systemic response to the general shortage of liquidity or purchasing power to solve

real-time problems.

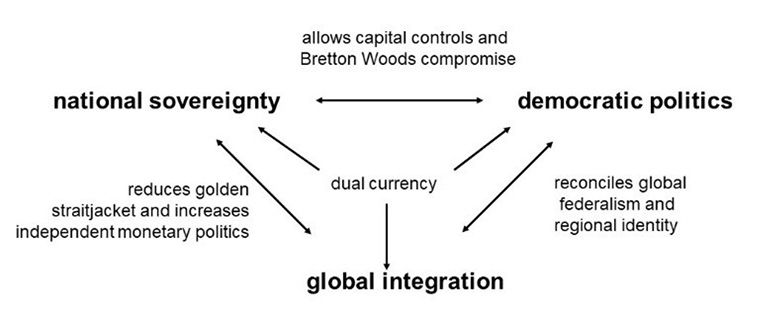

These trends are part of a response to the trilemma explained in this text. Such digital currencies operate in parallel, follow a different purpose, are generated in a different way, and run through a different technology (distributed ledger technology)11 than the given money system. Designed and regulated in the right way, this additional liquidity, injected into the market, would have the potential to meet requirements and reduce the golden straitjacket imposed on nation-states that follows from further economic integration. Such a dual currency system has the capacity to reconcile global market rules on the one hand and regional sovereignty and democracy on the other. A parallel monetary system such as this would also allow a partial control of capital in a Bretton Woods compromise, because the electronic money, operating through a smart contract, would be distributed to specific sectors or regions accordingly.

This conclusion is not obvious at first glance, but has significant implications for how to conduct politics in the Anthropocene, where geophysical planetary boundaries and ongoing interconnectedness lead to asymmetric shocks, non-linear tipping points, feedback loops and fat tail events—and this even when nation-states have done everything ‘right’. To note: the parallel currency system in question employs a pre-distributive mechanism, meaning money would be created to finance specific purposes up front. It could be implemented either top down, through an additional mandate of the monetary regulators and central bankers (called a CBDC, a central bank digital currency), or bottom up through corporations or regional/national public bodies (called regional complementary currencies or cryptocurrencies). In either case or a mix between the three, the required liquidity to finance business, social and ecological projects would not be generated via the redistributive mechanism we currently use, which follows the rationale of economic growth first and redistribution second. In fact, at present all social and ecological projects are primarily financed through taxes, fees or philanthropy. Because these monies stem from the revenue of global goods and services, this system represents an after-the-fact redistributive mechanism (‘end of pipe financing’). In contrast, dual currency systems offer additional parallel liquidity and can tailor business to regional requirements. While this conclusion is not immediately obvious, there is a rationale to it, even though some additional intellectual effort is required.

“As long as we cling to a monetary monoculture, democracy, national sovereignty and further economic integration will remain mutually incompatible.”

To be more precise: as long as we fail to question the design of the financial and monetary system and do not adjust it to the new requirements of politics in the Anthropocene era, the trilemma will remain unresolved. To focus again on extreme cases for the purpose of illustration: with a dual currency system in place, a nation or a region such as the EU could overcome the limitations of the trilemma. By having the ability to independently issue liquidity at a national, regional or corporate level to finance local, regional or global commons, the current golden straitjacket for sovereign nation-states (or the EU) would be removed or at least loosened. A dual currency would also affect a Bretton Woods-type compromise by establishing a form of capital control and a fixed or pegged currency regime between the two currency systems. The very nature of the design of the additional electronic ‘coins’ running through a smart social contract would restrict and therefore limit the flow of free capital towards desired goals. Lastly, such a dual currency system has the potential to enhance global federalism where needed and when politically agreed upon, as in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) endorsed by the world community in 2015.§ It would deepen economic integration by providing the additional liquidity and purchasing power required to energize the two thirds of the global population that are currently missing out on participation in globalization. Overall, it would offer governments the required financial leverage and political self-efficacy (including additional ‘green’ tax revenues) to tackle the numerous environmental, social, and political challenges we face as a world community. If we take this concept one step further, a dual currency system eligible for the payment of taxes and wages and running in parallel to the given conventional currency system would trigger a steering effect impacting business and public affairs. This steering mechanism would stabilize the pro-cyclical tendency of each monetary policy in an anti-cyclical manner and reduce illicit transactions. Additional positive externalities would be generated by direct investments into mitigating the negative externalities in the era of the Anthropocene. For example, each such ‘green’ dollar spent on the desired goals—whether the eradication of poverty, infrastructure development, improving access to healthcare or educational programs, or addressing global warming and the loss of biodiversity—would reduce short-term and long-term negative externalities and spillovers. In an era where everything is connected to everything else and everywhere, there is no longer any such thing as a ‘free lunch’. We need to take this into account.

4. Conclusion: Monetary Politics in the Anthropocene

Living in the Anthropocene means living in an interconnected world within planetary boundaries. This changes not only the way we study economics, but also the way we deal with (global) common goods, engage in politics, and do business—it even changes the way we reason. It is true that under the conventional regime of a monetary monoculture, trying to have fixed exchange rates, free capital and an independent monetary policy leads to financial instability. As long as we cling to a monetary monoculture, democracy, national sovereignty and further economic integration will remain mutually incompatible and we will stay trapped in the global trilemma. But money is not a natural law; rather, it is one of the most powerful human inventions to accomplish human welfare and wealth. It can be changed and adjusted, just like club rules or a marriage contract. The money system operates like a catalyst, enabling infinite transactions, and steering society as a whole towards good or bad. It has a quantitative aspect, measured in the volume of money injected and circulating in the economy, and a qualitative aspect, measured in what and where money goes and what it does.12 It will require intellectual courage, scientific clarity and a handful of bold political decisions to confront, change, and adopt this given system for the good of humankind.

‘Politics’ in its ancient Greek meaning (πολιτικά) referred to the process of making decisions that were relevant for the community as a whole. This definition still holds true in the era of the Anthropocene. It is not the commons or the environment that will determine whether we are able to achieve more wealth and lower negative externalities—a so-called Pareto-superior equilibrium—as human rights and fresh air will stay the same, regardless of the economic regime in place. Rather, the (mis-)alignment of the monetary system is crucial. In other words: it is the monetary system that will predetermine the outcome of the global trilemma—not directly, by rearranging the three components of the trilemma itself, but indirectly, through the introduction of a parallel currency. This will enable global federalism, a Bretton Woods-type compromise and the loosening of the golden straitjacket.

Creating such a monetary ecosystem by introducing an additional parallel currency would provide additional leverage for national sovereignty, democracy and deepening economic integration at the same time. It would then be possible to pick three and have them all. Whether we adapt a more top down approach (CBDC) or a more bottom up approach (cryptocurrencies or community currencies) or a combination of the approaches is then a political decision of its own.

Notes

- Marcelo M. Suarez-Orozco, Humanitarianism and Mass Migration: Confronting the World Crisis (Oakland: University of California Press, 2019)

- P. Crutzen, “Geology of mankind,” Nature 415 (2002): 23

- M. Obstfeld, & A M. Taylor, “The Great Depression as a Watershed: International Capital Mobility in the Long Run”. In Michael D. Bordo; Claudia Goldin, and Eugene White, (eds.). The Defining Moment: The Great Depression and the American Economy in the Twentieth Century. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), 353–402.

- D. Rodrik, Has Globalization Gone Too Far? (Washington, DC Inst. for International Economics 2005); D. Rodrik, The Globalization Paradox (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011)

- L. Oxelheim, International Financial Integration (Berlin: Springer, 2011)

- S. Brunnhuber, The Curse of the Carbon Bubble: How to Really Exit the Fossil Age, New hybrid financial engineering for a low-carbon economy in the 21st century UN Compact Year book 2019 (in press)

- T. Mancini-Griffoli et al., Casting Light on Central Bank Digital Currency (Washington D. C.: International Monetary Fund, 2018)

- B. Lietaer, The Future of Money: Creating New Wealth, Work and a Wiser World (London: Random House, 2012)

- Gill Seyfang and Noel Longhurst, “Growing green money? Mapping community currencies for sustainable development,” Ecological Economics 86 (2013): 65–77

- Garry Jacobs, “Cryptocurrencies & the Challenge of Global Governance,” Cadmus 3, no. 4 (2018): 109-123

- A. Tapscott & D. Tapscott, “How Blockchain is changing Finance,” Harvard Business Review March 1, 2017

- S. Brunnhuber, “How to Finance our Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Socioecological Quantitative Easing (QE) as a Parallel Currency to Make the World a Better Place,” Cadmus 2, no. 5(2014): 112-118

* World Bank 2012, “Foreign direct investment, net inflows (BoP, current US$) | Data | Table”. data.worldbank.org.

† UN, 2017, “International Migration report”.

‡ WTO, 2015, World trade and the WTO: 1995-2014. World Trade Organization: International Trade Statistics.