Hello Visitor! Log In

Mediation of Conflicts by Civil Society

ARTICLE | October 27, 2011 | BY Melanie Greenberg, Robert J. Berg, Cora Lacatus

Author(s)

Melanie Greenberg

Robert J. Berg

Cora Lacatus

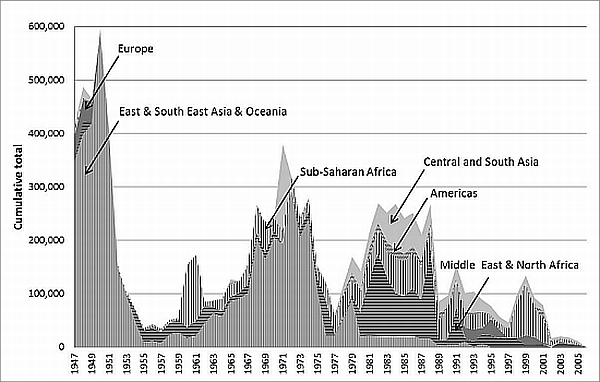

The number and severity of conflicts (violent clashes where there are more than 1000 casualties) have declined markedly since the end of the Cold War. This is shown graphically below despite this being a time of high population growth:1

Figure1: Number of reported, codable deaths from state-based armed conflict, 1946-2005

Even including a rise in the number of terrorist incidents, these trends hold true. 2

The Decline in the Level of Conflicts

The causes of this decline are threefold: Greater reliance on the United Nations; a far larger number of people who have stronger stakes in the stability of their societies; and far greater activity by civil society organizations mediating between potential and actual combatants. In addition, the normative landscape for conflict and intervention has changed considerably in the post-Cold War era. Norms about the appropriateness of using war and violence to resolve disputes have shifted, making it difficult for leaders to wage war with impunity. And Cold War era presumptions regarding the inviolability of national sovereignty have eased to allow for intervention under the mantle of the UN's "responsibility to protect."

Prior to the end of the Cold War, prolonged conflict often served the interests of the two major powers, the United States and the Soviet Union. One thinks of the Cold War battleground of Vietnam and the conflict in Angola that straddled the end of the Cold War. Where superpower standing was at stake, there was a common interest to prolong conflict, and to stoke the fires of local conflict in the name of Superpower rivalry. Hence there was often a shared policy of the West and East to by-pass the abilities of the UN to help reduce some of the main conflicts of the 1960s, 70s and 80s.

After the Cold War ended, it became the common policy of all the Permanent Members of the Security Council (the P-5) to turn to the UN to avoid conflict and to broker peace. There was a dramatic upgrading of UN Peacekeeping. From the end of the Cold War in 1989 to the present there has been a ten-fold increase in the number of peacekeepers, from 10,300 to the current level of 98,000 military plus 24,000 civilians. The number of peacekeeping missions increased from eight very modest missions to 16 more robust missions.3 Academic research bears out the overall effectiveness of peacekeeping operations in reducing conflict. The most recent Human Security Report summarizes recent findings, concluding that "an appropriately designed peace operation significantly improved the prospects for peace," and that the risk of war recurring "was reduced by at least half compared to post-conflict countries where there was no peacekeeping operation." 4

Accompanying this was far more active use of UN Security Council sanctions against aggressors; some institutional reforms to make UN peacekeeping more effective; the creation of the UN Peacebuilding Commission to make smoother the transition from conflict to post-conflict normalization (by moving in a coordinated way from emergency humanitarian help, to reconstruction help, to normal development help); and the creation of international criminal law against aggressors; and the establishment of special tribunals and the International Criminal Court. All of this considerably expanded the array of UN hard powers to reduce conflicts and the affects of conflict. The work of Paul Collier at Oxford demonstrated that without long term development and security assistance, conflicts have a way of re-igniting, and when they do the whole neighborhood of surrounding countries usually suffers greatly as well.5 So it is in the interests of national and regional peace to bind up the wounds of conflicted societies and this takes many years of concerted efforts. An important case in point is Afghanistan where repeated early leave taking by the international community has left the country prone to new conflict. Arguably the UN and other important parts of the international community are getting better in learning how to help societies move out of conflict and into sustained development. Cases in point are Sierra Leone and Liberia.

Certainly there are critiques about the UN's roles. Well researched proposals to improve the UN's peacekeeping operations (e.g., the 2001 report of the Panel on United Nations Peace Operations, known as "The Brahimi Report") have been neglected by the General Assembly due to almost trivial budget considerations. The process of creating ad hoc peacekeeping missions means throwing together all kinds of different military standards, procedures and linguistic groups and troops that have not trained together all under ad hoc command, rather than having a standing military (which the P-5 opposes). Alas, there has also been a number of well reported incidents of UN peacekeepers abusing civilians they are supposed to be protecting. But far better to have a variably functioning UN peacekeeping force than not to have one at all.

So today the UN has the second largest deployed military in the world, and is very often called upon to maintain peace.

The second main factor leading to a decline in conflicts has been the sharp rise of the middle class in countries that had been prone to conflict. Quantitative research has found "a very strong association between GDP per capita and the risk of war: high incomes are associated with low risks of war." 6

It used to be a cliché that no two countries ever got into conflict if they had McDonald's restaurants. The conflict in the former Yugoslavia put an end to that cliché. But the principle remains that people with higher and more reliable income are more apt to opt for peaceful resolution of disputes. This principle is not a stand alone. But it does operate as an important and measurable ingredient for peace. The World Bank's World Development Indicators data show that countries at peace have less poverty, better health, and higher growth than countries in and out of conflict.

The third factor is the least appreciated. It is the rise of civil society groups that help resolve conflicts. While UN peacebuilding, peacekeeping and mediation efforts have garnered wide attention in the media and academic writing, the proliferation of private conflict prevention and resolution efforts have remained far under the radar. In fact, there is a thriving ecology of groups working to prevent and resolve deadly violence at every point of the conflict spectrum, in every imaginable topography. These groups are local and international, and are found in all but a very few countries. The professionalism of these groups has been increasing markedly and their impact is profound. Why so? Why not leave peace to the diplomats? The answer is that diplomats certainly have useful roles, but they tend to deal with only a part of society (and they may be prevented by political considerations from actual discussion with potential or real combatants), and their key job is to keep relations with the party in power. Diplomats representing Great Powers usually are associated with the policies of the incumbents. In contrast, civil society groups can work as neutral entities with both or all sides in a potential or real conflict. They are not wed to a fixed national position. They are wed to finding what can work to allow peoples to live together in peace.

Civil society groups perform a number of useful functions, both in preventing and resolving conflict. While the groups we mention here are largely American and European, working with local partners, a huge variety of civil society organizations of all nationalities work in conflict zones around the world. *

- Early Warning: Civil society groups can voice an alarm when situations are deteriorating. The best known such service is CrisisGroup (formerly known as the International Crisis Group), which regularly reports on leading signs of the erosion of peace and cases of rising risks of conflict. A parallel service is Refugees International, which alerts the global humanitarian and political communities when there is a rise in refugees (often a sign of severe upcoming conflict). The ENOUGH Project and the Genocide Intervention Network serve as advocacy organizations, alerting US government officials about imminent genocide in Africa, and building political will for intervention.

- "Structural" conflict prevention: An increasing number of groups work very far back in the conflict spectrum, striving to develop strong local institutions that can resolve conflict long before actual violence breaks out. Some of these groups might not even identify themselves as conducting "peacebuilding" per se, but nonetheless carry out activities that lead to stronger and more resilient societies that are less prone to violence. The development organization MercyCorps, for example, embeds conflict prevention into its development work, targeting groups like young men who might otherwise be drawn into violence, and providing jobs and education. Search for Common Ground develops media strategies for better relations between ethnic and political groups, including a long-running radio soap opera in Burundi. Partners for Democratic Change has offices around the world dedicated to strengthening communities' ability to manage change, maximize the benefits of diversity, and prevent and resolve conflicts.

- Conflict Resolution: A huge range of civil society groups works in societies either undergoing or immediately threatened by outbreaks of deadly violence. Some groups like Crisis Management Initiative and Humanitarian Dialogue offer mediation services at a "second track" level outside governmental channels, and have worked in areas as diverse as Aceh, Somalia and the Philippines. The Public International Law and Policy Group offers legal representation to parties in actual peace negotiations, and serves on the ground in conflict areas around the world to avert election violence (Kenya, Nepal) and promote rule of law (Tanzania, Somaliland). Other groups, like Conciliation Resources and the Institute for Multi-track Diplomacy, work with civil society organizations to develop strategies for influencing governmental behavior or changing conflict dynamics. 3P Human Security works in Afghanistan on civil-military dialogue, and prepares civil society groups to engage in discussions about long-term peace in Afghanistan. BEFORE works to avert election violence in Guinea and Guinea-Bissau.

- Post-Conflict Peacebuilding: While it is not always easy to separate conflict prevention from post-conflict peacebuilding, an increasing sector of the field is working to re-build war-torn societies, and to prevent a descent into violence. The period after a peace agreement is signed is often the bloodiest time of a conflict, and these groups focus on easing this transition. The Project for Justice in Times of Transition assists leaders in divided societies struggling with conflict, reconciliation and societal change by facilitating direct contact with leaders who have successfully addressed similar challenges in other settings. The International Center for Transitional Justice provides technical assistance for countries establishing truth and reconciliation commissions, and other forms of post-conflict judicial processes.

- Dissemination of theory into practice: Peacebuilding is a field driven to an unusual degree by ideas, with robust interaction between academics and practitioners. Under the cover of academic research, many universities offer peacebuilding services, holding conferences and bringing warring groups together for reflection and the development of new ideas for resolving conflict. George Mason University's School of Conflict Analysis and Resolution, Harvard's Program on Negotiation, Syracuse University's Program on the Advancement of Research on Conflict and Collaboration, American University's International Peace and Conflict Resolution Program, and Brandeis University's Co-Existence Program are but a few of the peace-oriented academic programs training the next generation of practitioners, and carrying on quiet but dynamic conflict intervention.

Future Trends in Peacebuilding

The active involvement of civil society in peacebuilding shows no signs of abating. In addition to areas of current interest, we predict three areas of increased growth for peacebuilding: a systems approach to peace; the more active engagement of women in peacebuilding; and a stronger focus on the links between climate change and conflict.

-A Systems Approach to Peace

A tremendous challenge for the peacebuilding community to date has been to realize the collective impact of groups intervening in the same conflict arena. Typically, diplomats do not communicate with military actors or civil society groups; civil society groups do not communicate with one another; and actors working in a range of substantive areas - from environmental security to public health to development - do not reach across disciplinary lines to analyze how they might cooperate more effectively for joint gain. One of the most exciting areas of change in the conflict resolution field is the development of a "whole of community," or "systems" approach to peace. In a whole of community approach to peace, each level of peacebuilding practice interacts consciously with every other, sharing information and dividing labor to form a more efficient overall strategy. Operating at a systems level allows policy makers and practitioners to more fully understand complex conflict environments, find the linkages that should be made between programs, identify leverage points where impact can be amplified, and set the most compelling priorities for action.

-Women's Participation in Peacebuilding

A second area of growth in the field is the burgeoning role of women in fostering peace. While women often form the backbone of civil society organizations working toward peace, they are vastly underrepresented as mediators, and as governmental parties signing peace agreements. A typical experience for countries in conflict is for women leaders to work for peace, sometimes decisively and very often with high risk and amazing dedication, only to be quickly subordinated by men at the bargaining table, and in post-war reconstruction efforts like demobilization, disarmament and re-integration programs. This was the common situation in the struggles for renewed national life in Eastern Europe when the Soviet empire was dissolving, and has been found through the range of African conflicts, an exception being Liberia where women were decisive in forcing a peace agreement and then instrumental in obtaining political power.

United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 of October 31, 2000 called upon all nations to increase representation of women in all decision making levels (national, regional, international) to prevent, manage and resolve conflict; and called upon the UN to involve women at all levels in these processes and in peacekeeping operations. The rather remarkable creation of UN Women, a major organizational reform of the UN approved last year, has reinvigorated interest in and action on 1325. Far more attention is also being given to making sure women are represented at the peace table, as parties and mediators, building on a very weak base of seven percent representation. And sexual violence is finally being recognized as a war crime and treated accordingly by peacekeepers, military actors, and tribunals. In short, the motto of a major new USAID program on women in peacebuilding is apt: "Nothing about them without them." The Nobel Peace Prize Committee apparently agrees given their 2011 awards.

-Peace and Climate Change

The peacebuilding community - at the governmental level and the civil society level - is increasingly recognizing the links between climate change and conflict. The Darfur conflict, for example, was properly treated not only as a crisis of governance and violence, but also as an ecological disaster - increasing desertification caused by global warming led to clashes between nomadic and pastoral tribes, who now needed to compete over decreasing amounts of arable land. Many organizations are already helping parties mediate over scarce water supplies, devising creative solutions to scarcity in watersheds ranging from the Middle East to the Himalayas. Negotiating over water has even been called "The Blue Peace," with the idea that countries that cooperate over water resources will be less likely to fight over other issues. Conflict prevention operating at the margins of ecological change will only increase in the coming decades, bringing a range of scientific expertise, novel conflict resolution techniques, and new forms of cooperation.

-Interest of the World Academy of Art and Science in Peace

Working for peace is part of the heritage WAAS fellows have been given by Academy founders who, after helping develop the theories and technology for nuclear weapons, were amongst the first to recognize that they should be banned. Two of the seven founders of WAAS (Robert Oppenheimer and Bertrand Russell) became global figures in proposing nuclear disarmament. A charter member of the Academy was Joseph Rotblat, founder of the Pugwash Conference on Science and World Affairs, a group very active since its creation on nuclear disarmament. Rotblat was the official liaison between Pugwash and WAAS.

In the Academy's first substantive endeavor, Science and the Future of Humanity, Oppenheimer spoke with regret about the development of the bomb and said that only by discovering our common humanity and by making education available to all can we become a world with a positive future. He sketched out why one needs science and the arts together. He said "For the artist and the scientist there is a special problem and a special hope, for in their extraordinarily different ways, in their lives that have increasingly divergent character, there is still a sensed bond, a sense of analogy. Both those of science and of art live always at the edge of mystery, surrounded by it, both always, as the measure of their creation, have to do with harmonization of what is new with what is familiar, with the balance between novelty and synthesis, with the struggle to make partial order in total chaos. They can, in their work and in their lives, help themselves and one another, and help all humanity. They can make the paths that connect the villages of arts and sciences with each other and with the world at large the multiple, varied, precious bonds of a true world-wide community."

A number of notable Academy figures continued work on nuclear disarmament and peace. In 1964 the Academy focused on Conflict Resolution and World Education. The theme was that a culture of peace had to be a major global effort. Similar activities took place in the following two decades.

- In 1989 the International Commission on Peace and Food was constituted by Fellow Garry Jacobs and for eight years the Center it established was chaired by former Academy President Harlan Cleveland.

- Its work influenced thinking in the Academy on the issues. In the mid-1990s there was an effort aimed at the Balkans on Tolerance, Science and the Modern World.

- An international symposium on peace and development was held under Academy auspices in New Delhi in 2004. A series of roundtables began in 2005 involving Harlan Cleveland, Robert McNamara, Air Commodore Jasjit Singh, and a half dozen other Fellows, focusing on the safety risks of nuclear weapons. Late in 2005 the Academy held a NATO-sponsored workshop on nuclear safety and disarmament issues in conjunction with its 2005 General Assembly in Zagreb. As an immediate follow up, the Board created a Standing Committee on Peace and Development Studies with Garry Jacobs as Chair.

- In 2006 the Academy mobilized very significant financial support that enabled the Global Security Institute to gather a large number of top representatives of Middle Powers which urged the nations holding nuclear weapons to disarm. They called nuclear weapons a threat to their own nations, thus widening the rationale for disarmament.

- In 2007 the Academy published through the World Futures Society a detailed guide on security and nuclear disarmament.

- In 2008 the Academy helped sponsor a global contest among youth and a conference of the winners of "Students for a Nuclear Weapons Free World," organized by the World Federation of United Nations Associations.

- Also in 2008 WAAS Fellow Jasjit Singh organized with India's Ministry of External Affairs an important conference of Indian leaders and other Academy Fellows marking the 20th anniversary of Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi's historic speech at the United Nations calling for complete nuclear disarmament. Prime Minister Manmohan Singh keynoted the conference. The conference proposed a comprehensive concept of cooperative human security encompassing military, political, environmental, food, energy, employment and financial issues. This was followed up later in the year at the 2008 Hyderabad General Assembly with panels. Subsequently, Prime Minister Singh formally took up Rajiv Gandhi's proposals as a key part of his Government's foreign policy.

- In February 2011, the Academy met with Indian security officials and academic experts on nuclear disarmament issues. At the conclusion of the meetings the members of the Academy's Standing Committee on Peace and Development wrote on their behalf to India's top political leaders about the important safety issues in nuclear weaponry and the need for negotiated safeguards.

Implications for the Future Work of the Academy

Particularly in the 2008 Conference in India involving top governmental leaders and in the linkage within the Academy of Peace and Development, there is clear understanding of the complexity of finding and holding peace in areas of conflict. New learning from civil society on 'Whole of Community' approaches to building towards peace has not yet been formally applied to help establish the pre-conditions for successful nuclear disarmament between states. There are other implications for the Academy by these developments:

- We should take advantage of this new learning to think through our own strategy to foster nuclear disarmament and to then articulate an updated strategy. This new learning calls for more complex and longer term strategies.

- We could usefully partner with talented civil society organizations expert in peacebuilding or networks of such organizations.

- Women need to be integrally involved in both the strategy and in the participation of Academy programs working for peace.

- Our strategies should aim to involve parties on both sides of disputes to help think through and act on whole of community strategies.

- The Fellowship of the Academy should be bolstered by experts (of both genders) from the peacebuilding community.

- Missing from both the peacebuilding and the nuclear disarmament strategies are focused use of electronic communications and media. More modern means of meeting and linking need to be explored in our strategies.

- Further down the line, the Academy might well be a neutral ground to bring together the peacebuilding and nuclear disarmament communities to explore how the learnings from both groups could enrich the other, and to promote collaborative initiatives involving both groups.

It has been over fifty years since the founders of the World Academy urged work on nuclear disarmament. There has been progress, particularly between the US and Russia, but it has been slow in coming. Rather than reducing, we have seen an increase in the number of nuclear powers, a setback for the Non-Proliferation Treaty. The Fund for Peace's Failed State Index indicates that the potential for war and massive loss of life threatens a number of important states, including a nuclear power. All this should add urgency to our work. Fortunately, new learning creates new opportunities to further the Academy's long term interests in fostering peace and development.

Notes

- Human Security Report Project, Battle Deaths from State-Based Armed Conflicts by Region, 1946-2007. Retrieved from http://www.hsrgroup.org/our-work/security-stats/state-based-battle-death...

- Andrew Mack, "Global Political Violence: Explaining the Post-Cold War Decline," International Peace Academy Working Series, 2007.

- Peacekeeping Fact Sheets, United Nations http://www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/resources/statistics/factsheet.shtml

- Human Security Report: The Causes of Peace and the Shrinking Costs of War (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009/2010), 70.

- Paul Collier, Wars, Guns, and Votes (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2009)

- The Real Wealth of Nations:Pathways to human development (Geneva: UNDP, 2010), 3.

For a full listing of Alliance for Peacebuilding members, all of which work actively to prevent and resolve conflict worldwide, see www.allianceforpeacebuilding.org.

- Login to post comments