Hello Visitor! Log In

The Market Myth

ARTICLE | April 22, 2016 | BY Tomas Björkman

Author(s)

Tomas Björkman

Abstract

The Market can be understood as a self-organizing system that is constantly evolving. Like all social institutions, it is governed by principles and rules created by society, not by any universal laws of nature. If it does not work the way we want it to, we have the power and freedom to change its rules. However, prevailing notions about the market are veiled in myth. Many have argued that there is a vast gap between economic models of how the market is assumed to work and how it actually functions, but there is also a gap between the way it now functions and alternative possible ways it could be structured to more effectively promote social welfare and equity. ‘Unveiling the myth’ is therefore necessary to alter its enduring influence on us, for the betterment of humanity. Some have referred to this myth as ‘neoliberalism’, but this is not the emphasis here. The point, rather, is to show that understanding theories and models of the market in terms of the seven myths discussed in this article allows us to change the constitutive rules of the market and radically improve the pre-distribution of social benefits while preserving the dynamic freedom of the market, thus limiting the need for regulating rules.

1. Introduction

The word myth is used in two main ways that are often conflated or confused:

- A widely held but false belief or idea.

- A traditional story—a narrative—especially one concerning the early history and enduring purpose of people or one explaining natural or social phenomena, typically involving supernatural beings or events.

The market fulfils both of these meanings. First, it is a myth that the market produces fairness or that it maximises the common good. We will come across a number of other myths of this kind; things most experts know are wrong but which we somehow keep believing as “folk-knowledge” about the markets. Second, the market is also the “big story”—the meta-narrative—of our time: it’s the story that explains the foundations of our new global world. It even involves supra-physical forces like the so-called ‘invisible hand’.

The first meaning of the myth is obvious. We dismiss stories as myths all the time. The second meaning is more interesting. This is the meaning, for example, of the myth of the creation of the world or the Tower of Babel. When we say these are myths, we are not necessarily dismissing them as false. We are saying they are not necessarily true in the narrow sense that the Battle of Hastings is an historical fact. We are saying that they are important stories that help us make sense of the world, of life and of our human predicament. Human beings need meaning, and the myths we construct about life help us to put a symbolic frame around our reality so we can find structure and meaning in an otherwise chaotic and random existence.

“The market like every other social institution is a product of our conception and invention and if it does not work the way we want it to, we have the freedom and power to change it.”

The Cambridge University Reader and the World Bank economist Ha-Joon Chang highlights the way these new myths, just like the old religious myths, are insulated from factual reality:

“You have to know that academic economists today are not even interested in the real world. In the economics profession today, interest in the real world is an indirect admission that you are not very good. If you are really smart you do really abstract mathematical modeling. If you are a bit less good you do econometrics, basically manipulating statistics. If you are really down in the pits you are interested in the real world…It’s a strange academic culture… when you say these uncomfortable things, people refuse to listen to you.”1

In the transitions from the Renaissance to the scientific revolution, to the Enlightenment, to full-blown modernity and its post-modern critics, we see our place in the universe being pushed farther and farther into the periphery of reality itself; we are no longer God’s chosen children, not at the centre of the world, and even our emotions, thoughts and choices are beyond us—our sense of free will is considered an illusion. At the same time, in what seems to be a strange and wonderful paradox, each time we are dethroned by the history of science, we rise above our previous understanding and become—usually unwittingly—more intimately involved in co-creating the natural, inner and social worlds, both external/objective, internal/subjective and social/inter-subjective reality.

If we want to reduce the savage inequalities and insecurities that are now undermining our economy and democracy, we shouldn’t be deterred by the prevailing myth of the ‘free market’. The central message of this essay is that the market like every other social institution is a product of our conception and invention and if it does not work the way we want it to, we have the freedom and power to change it. We can only do that when we overcome the conceptual illusion of the false dichotomy between a “free” market and a “regulated” market. We need not conform to the limitations of the current market system. We can make the system even more efficient and just. There is no inherent conflict between these two fundamental aims. We need a revolution in Economics as momentous as the one unleashed by Copernicus but in reverse. We need to fashion the future of economy on the principle that human beings are sovereign, and need not be subject to ‘the market’ as if it were a natural feature of the world outside of their collective control.

2. Myths of the Market

I have set out below what I believe are seven key myths—in the sense of false beliefs—of the market. These are not the only false beliefs that society holds about the market, but they are arguably the most dangerous ones. They are part of a bundle of propositions, shared perhaps most strongly by economic policymakers—possibly the group of people farthest from the frontline of business. Together, these type one myths about particular features and functions of the market are subsumed and thereby shielded from criticism from the type two myth of ‘the market’ as a shared societal given.

Myth #1: The invisible hand makes sure that the market is fair and maximises the common good in society.

Myth #2: The market takes care of long-term interests, and it does so by taking everyone’s interests into account.

Myth #3: The market creates diversity and freedom of choice.

Myth #4: The agents in the market are rational decision-makers maximising their individual ‘utility’.

Myth #5: The market tends towards equilibrium where supply and demand meet.

Myth #6: Private for-profit corporations will always be the best organisations for maximising efficiency and creating wealth, and their way of functioning can never be changed.

Myth #7: That the ‘free’ market is a natural system.

3. Origins of the Myths

Where did these myths about the market come from, the false beliefs that fuel the rhetoric of politicians and popular sentiment about economics? A number of world-changing key historical events and influential individuals came to create the fertile soil for the myths; the result of which we harvest today. We will here look briefly at two of these influential persons—Adam Smith and Friedrich von Hayek—and some interesting historical incidents.

Adam Smith, who was to become the founding father of modern economy, met in 1750 with the philosopher David Hume, a key player at the dawn of the Scottish Enlightenment. Hume was enormously influential in Smith’s construction of economic theories. Hume did not believe in causation—at least he was sceptical about whether you could ‘see’ what causes what under a microscope—and Smith likewise fell back on an economic “mystery” of a crucial unseen ingredient, which he called the ‘invisible hand’.

Smith also taught rhetoric. His choice of the ‘invisible hand’ was to describe what was happening in what he called a “more striking and interesting manner”.2 The economics professor Warren Samuels investigated the original meaning of the phrase, arguing that contemporary economists had misunderstood it.3 They have interpreted Smith as if he were calling for less government or regulatory intervention, due to the self-regulation of “the invisible hand” when he on the contrary unambiguously demanded regulation to defend property and for the defence of the poor against the rich. Smith had in his sights supporters of the prevailing doctrine of ‘mercantilism’: the idea that economic trade is a zero-sum-game and that each nation needs to protect its own market at the expense of other nations.

“Smith provided a spirited attack on mercantilism for its extraordinary restraints, but he did not extend the attack to government and law in general,” writes Samuels.4 “Indeed, many of those who do extend the attack, wittingly or otherwise, are silent about Smith’s candour.” So, Smith was arguing for free trade but realised that the market is very dependant for its functioning on the formulation of its rules and that these fundamental rules need to take the interest of the poor in mind.

The difficulty for us now, two centuries later, is that Smith’s insights have settled in the minds of those who rule us in ways that are alien to what he meant. We are confusing Smith’s arguments about free trade with a mythical free market mysteriously free from any rules at all. This is one important origin of the Myth.

Another very important historical event in the creation of the Myth occurred in 1947 when the Austrian economist Friedrich von Hayek arranged a conference that launched an academic society that was to become influential enough to shift the way at least Western leaders viewed economics. This was to be known as the Mont Pèlerin Society.5 It was at this conference that the neo-liberal market myth was first spun in its current form.

Hayek’s manifesto, The Road to Serfdom,6 was published in 1944 just as the allied forces were liberating Europe, and was aimed at the post-war world. Hayek respected the economic authority John Maynard Keynes, whose theories seriously challenged the old so-called “neo-classical view” of the 18th century economists. Hayek, having his own “neo-liberal” agenda, did not challenge Keynes’ ideas until after Keynes’ death in 1946. At that point, however, Hayek invited 36 friends and allies to meet him at the Hotel du Parc in Mont Pèlerin, near Vevey in Switzerland. There, in April 1947, he and his influential friends Milton Friedman, Karl Popper, and Michael Polanyi discussed the defence of what they called “liberalism” in post-war Europe. Their aim was political rather than economic and they thought that the old neo-classical economic theory could, in a twisted way (as will see), be made to prop up a policy of general non-governmental intervention: the ideological agenda of Hayek. The foundation for a systematic revival of the old neo-classical economic thinking was thus laid.

The events in Mont Pèlerin in 1947 demonstrate that the concepts and rules of the market are under discussion, and can be changed through systematic effort. It is a strange paradox—and it lies at the heart of the story—that those who proclaim that markets are natural phenomena, which should not be manipulated or shaped, are themselves shaping markets day-by-day! I am an enthusiastic participant in open markets, and in principle I don’t believe we should put up barriers that make it more difficult to do business. However, we risk losing the real quality and value of the openness of markets if we don’t understand what ‘markets’ are, how they change, and why they need to change.

The Mont Pèlerin Society was born and continues the same work to this day, and meets at the same hotel every year. In small steps it launched a movement in economics that has become the new orthodoxy. It has been transmitted partly through academics with Chicago in the lead and partly through think tanks like the Institute for Economic Affairs in the U.K. and the Heritage Foundation in the U.S., founded by two Republican staffers in 1973. It was those staffers’ ambitious document Mandate for Leadership that was handed to top Reagan official Ed Meese just two days after Ronald Reagan’s election to the presidency in 1980. By 1982, there were leaders committed to the ‘neoliberal’ economic agenda in the U.K., U.S. and West Germany, and the victory of Mont Pèlerin was all but complete. The rest, as they say, is history.

4. The Myth, the Model and the Market

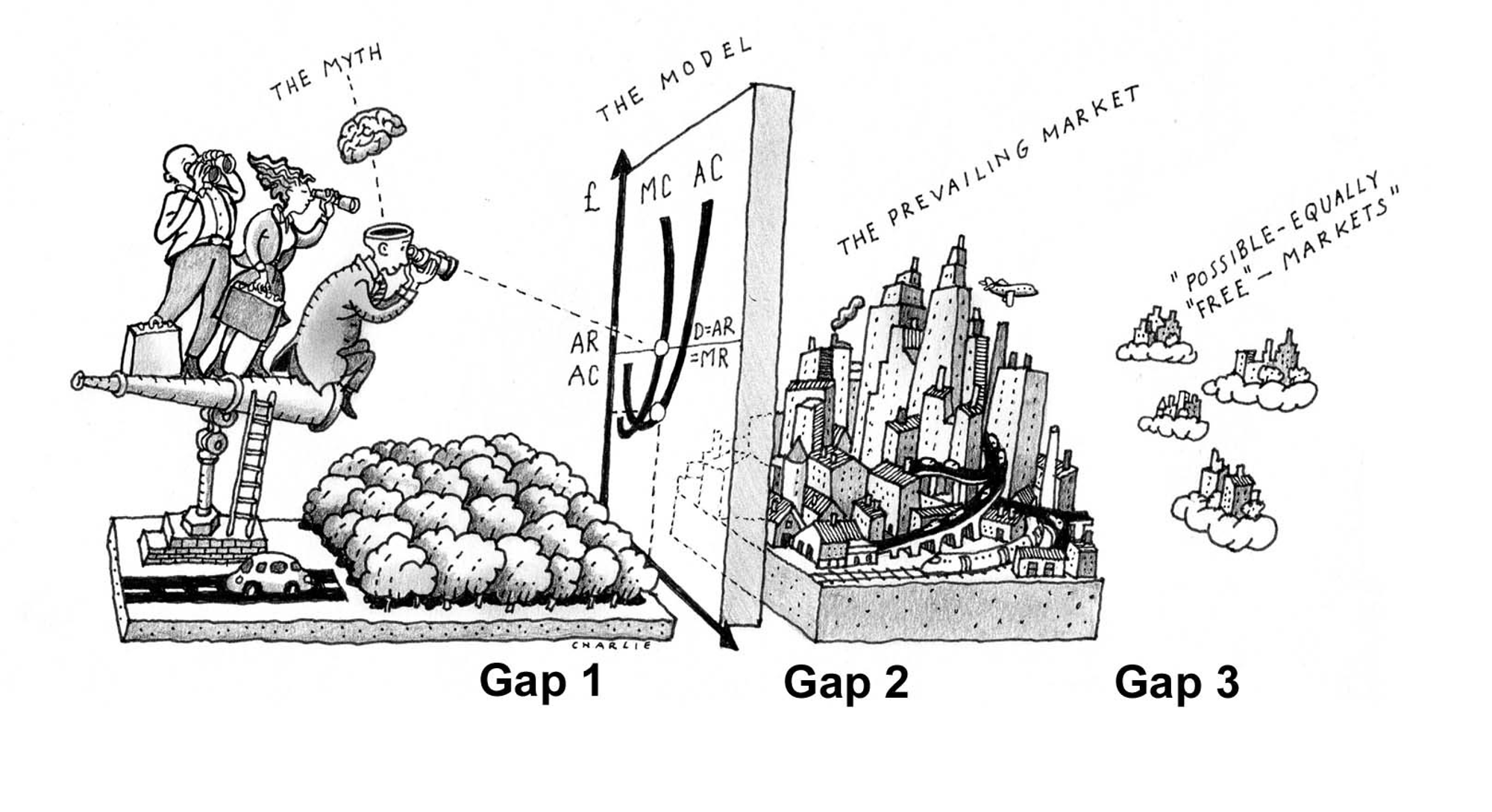

There is not just one yawning gap between the myth of the market and the market as it exists; in my view there are at least three.

Consider the figure below. Between the Myth and the Market, there is a third peculiarity: the neo-classical Model of the market—the way the market is supposed to fit the mathematical language of economists. We have to understand the gaps between all three: the common understanding (the Myth), the prevailing model of the market (the Model), and the real market, in all its multifarious complexity (the Market).

Then there is a third gap, between the Market as it is now and the Market as it could be—between the actual and the possible. It is into each of these gaps that the distortions creep.

"Our collective failure to see that the market is a contingent social construct gives rise to myths that treat the market as a fixed reality."

Gap 1: between the myth and the model. The myth of the market, our common understanding of it, is a very crude picture of the prevailing academic ‘neo-classical economic model’. In fact, there is a huge gap between what the model is actually telling the economists and what we as the general public tend to believe it is telling us. Such beliefs are often not explicit, as we have seen, but creep in as underlying assumptions in language and policy making. Examples include forgetting that the model only works for private goods, overstretching it by somehow believing that the market could take care of public, sometimes called collective goods as well. Or not understanding that the so called “Pareto-optimal” distribution that the model predicts is not very “optimal” at all, and definitely does not make any claims of being in any way a just or equitable distribution. Or that the “perfect market” that the model refers to is just a set of rather unrealistic mathematical assumptions necessary for the model to work, not some perfect ideal that the real market should aspire to.

One could say that this gap 1 is really an unnecessary gap based on confusion of language and misunderstanding of the predictions of the neo-classical model. The effects of this gap are myths like #1, #2 and #3 above that are all unnecessary misunderstandings of what the neoclassical model actually predicts.

Gap 2: between the model and the prevailing market. Then there is the other gap between the neo-classical economic model of the market and the real market. All economists know that the neo-classical model is not based on the real market. However, we tend to forget the very specific assumptions made in this model, and also the very limited scope within which the model has predictive value. The model is based on a set of very limiting assumptions of a ‘perfect theoretical market’. How far these assumptions are true for the real world is indeed debatable. More and more recent research into the assumptions shows that they are utterly unrealistic. We can do nothing about this gap; it is necessary for the model to work in theory. The problem is that we tend to confuse these crude but necessary assumptions for real facts about the market. We start to believe that a good consumer actually is rational, or at least ought to be. We start to believe that we all could be fully informed if we just try hard enough. We might even start to believe that it is acceptable in the market to only act out of self-interest and that the “invisible hand” takes care of the big picture.

The neo-classical model needs these assumptions to work. But we should remember that they are only assumptions. When we mistake them for facts we get myths that are based on the confusion of assumptions and facts.

Gap 3: between the prevailing market and other possible markets. We make yet another mistake about the market: we assume it is a fixed reality when it is in fact man-made through a complicated, contingent, historical process that is still on-going. The gap here is between the prevailing market as we know it and other kinds of market there could be—markets that might look very different and work very differently. This is the gap between the existing market and possible markets.

Our collective failure to see that the market is a contingent social construct gives rise to myths that treat the market as a fixed reality.

5. The Neo-classical Model

It should be noted that economic models in general are not designed to model the actual world. They are designed as a way to investigate what insights a number of theoretical assumptions and abstractions might lead to.

The originators of the neo-classical model did not make a blunder. They were not under any illusions about its links to reality, or lack thereof. The problem is that outsiders to economics are usually not really aware of tenuous assumptions on which the model has been built, and even economists often confuse their models for the way the real world works. As a result, they misinterpret these theoretical models, and incorporate them into the meta-narrative that supports the official worldview of the West—the myth.

It is difficult to look more closely at the myths, because doing so seems to undermine important foundations of our worldview. There are incentives, economic, political and academic, to stick to the prevailing view. In the language of mental developmental theorist Robert Kegan,7 it is not so much that we have this worldview—in the sense of freely and flexibly choosing it—it is more like this worldview ‘has us’ in the sense that it shapes the structure of our attention, our perception of value and our sense of the possible.

Despite this mental limitation of ours, the neo-classical model of economics is coming under attack these days. In response to these detailed attacks, many economists have insisted that critics provide an alternative “scientific” theory. Doing so, they don’t seem to realise how much their own model uses metaphors to build theories.

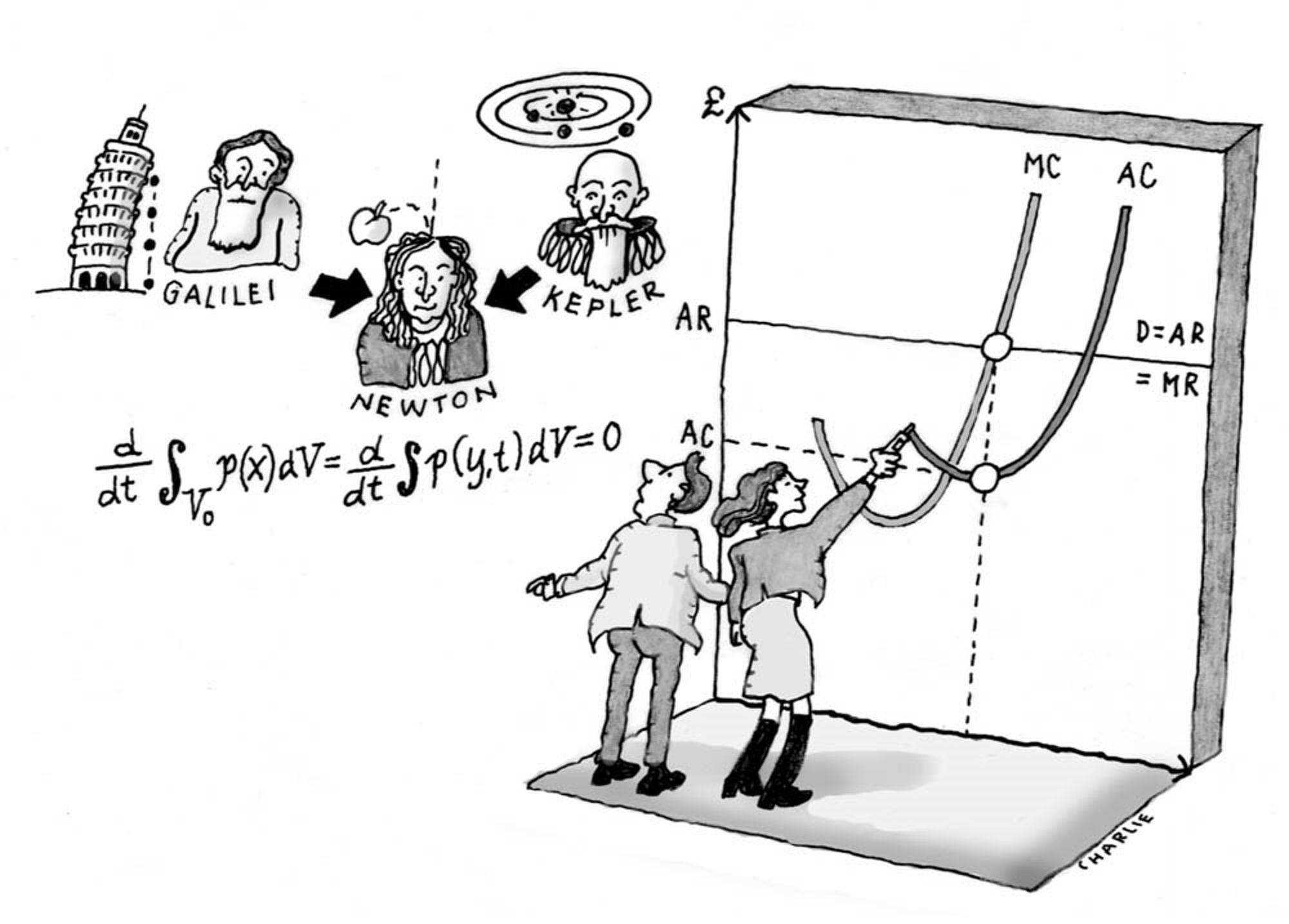

For example, many economists don’t understand how much their economic thinking has been bounded by the Newtonian language, and by their search for natural laws of the economy that work alongside the Newtonian laws of mechanics. The elegant synthesis of Galilean terrestrial mechanics and Kepler’s celestial mechanics into simple mathematical formulas expressed in Newton’s newly invented mathematical language of calculus came to be the lodestar for every science during the 1800s. As I elaborate in my book The Market Myth,8 the neo-classical economists sought, very understandably, to express economic phenomena in the same, very potent language of calculus.

The neo-classical economists knew what they wanted: a simplified model of the market that could be expressed in the mathematical language of Newton. They also knew that to succeed, they had to make unrealistic assumptions about the operation of the market. Some of these assumptions we now mistakenly hold as truths about the market. They wanted a mathematical model of Adam Smith’s faith in the invisible hand that self-organizes the economic system.

Had the 19th century economists had the computer tools we have today to model complex self-organizing systems, they might have opted to use those tools instead. But they did not have them, and they did as good a job one could do given the tools available in their time. But we have to remember that Newtonian calculus is not at all made to describe a complex system. It can actually only handle very simple systems, like two bodies moving under the force of gravitation. If we in this example add a third body, the Newtonian power of prediction breaks down.

To succeed in making a Newtonian model, they actually had to make a number of assumptions that simplified economics, fully aware that they were not quite real. In order to arrive at a model that could be expressed in the mathematical language that has been so successful for describing nature through physics, they had to make massive simplifications. They had to assume for example, as we will examine below, that all actors in the market are perfectly rational, that there is perfect competition and that all market actors are fully informed about everything going on in the market.

6. Interlude

Am I kicking in an open door here? Are not all students of Economics 101 told these days, to remember that ‘it’s just a model’? It is true that very few people would today explicitly subscribe to an unproblematic application of the model to the real world (whatever the ‘real world’ may be). Yet it somehow sneaks in, as we have seen, into public consciousness and becomes a myth. I would even venture to claim that many intelligent and well-informed individual scholars, citizens and policy makers, are together moved by a malignant invisible hand—towards preposterous conclusions and dire analytical fallacies, with resulting pathologies and instabilities in the market and society at large. The false belief in the model resides within the walls and pillars of our daily institutions, rather than with the individual student of economics.

“The neo-classical model of the market assumes that the operation of the market, just like planetary motions, is fixed once and for all, with given “utility functions”.”

So, what are the unrealistic assumptions of the model? Well, the model assumes that consumers are predictable, perfectly rational and conscious in their decisions. It assumes that they act from self-interest, are completely clear about what they want to buy and that they do not change their decisions.

It assumes that goods bought and sold in the market are private goods, owned by individuals and can be traded. It runs into difficulty when it comes to collective goods, sometimes called public goods, like military defence, culture or clean environment.

It assumes there is perfect competition, with a broad range of products from different suppliers competing on price and quality. It assumes there are always alternatives readily available in the market. It assumes perfect information, and that consumers and producers have access to all information about the item and of any alternative choices, as well as the infinite knowledge and time to evaluate it all. It assumes all actors in the market can predict the future consequences of their choices.

It is important to remember that all the above assumptions are made in order to make the model expressible in simple analytical mathematical language. The assumptions are not statements about the actual market; they were never meant to be. The idea that they are actually statements about the real market is one of the main reasons for the myths around the market: see gap 2 above.

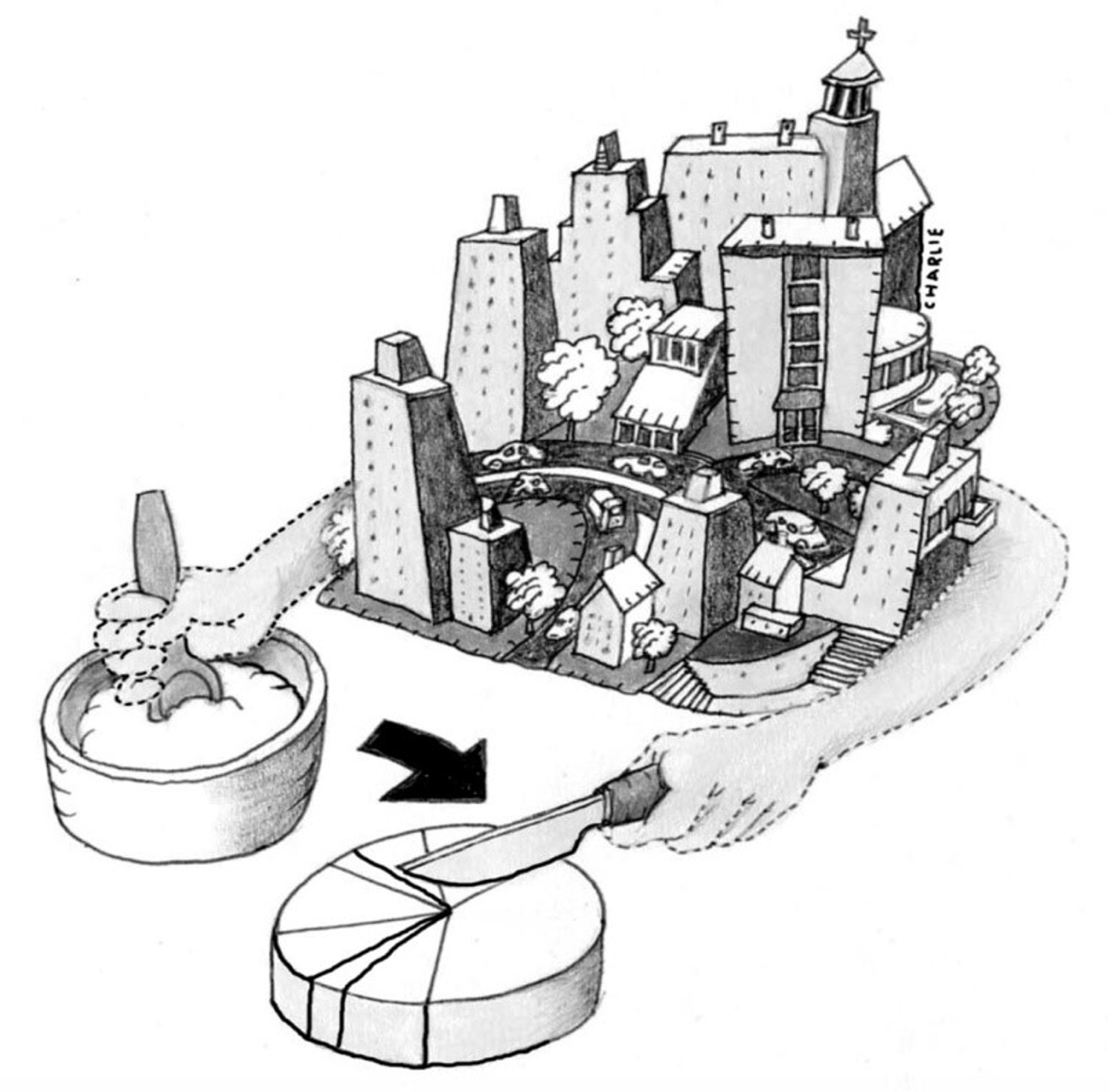

7. The Market as a Man-made, Self-organizing System

Adam Smith was right; the market is a complex self-organizing system. But we have to realize that, in contrast to the many natural self-organizing system we learn about in biology,9 it is a man-made self-organizing system with a particular history that could have been different. The neo-classical model of the market assumes that the operation of the market, just like planetary motions, is fixed once and for all, with given “utility functions”. But the market system is fundamentally different from physical systems. Not only in the sense that it could be regulated from the outside with regulating rules, but also in the sense that the constitutive rules, the rules that by definition are necessary to even have a self-organising system in the first place—like property rights and qualifying market agents—are man-made constructs.

This distinction between these two kinds of rules governing systems was introduced by the philosopher John Searls,10 to mark the ontological difference between rules of a socially constructed system or game that are necessary for there to be any game in the first place—like the rules that determine the movements of chess pieces in a game of chess—and rules that regulate the game once it is operating—like setting a time limit to a game of chess or a price regulation in the market.

With this distinction we realize that even a market free from any regulating rules will always need constitutive rules to start self-organizing. In a natural self-organizing system these constitutive rules are the feedback loops governed by physical constants or chemical reaction patterns that we humans can do nothing about. But for any social self-organizing system like the market, those constitutive rules can be implemented in many different ways: with very different self-organizing outcomes as result. Examples of constitutive rules include any definitions of property rights or corporate rights. The outcome of the market’s self-organising process that Adam Smith called the “invisible hand” will therefore be dependant on the specific formulation of the constitutive rules. Hence, even the “free market” is always man-made. “Just how God or nature determine the strength and direction of gravitational forces, man determines the strength and direction of market forces.”

8. The Two Invisible Hands of the Market

Different constitutive rules will result in different market outcomes both with respect to the amount of goods produced and their distribution. One would therefore want to construct the constitutive rules in a way that maximizes the efficiency in production and promotes a distribution of wealth that is considered fair. Once the constitutive rules have been optimized there might still be need to impose regulating rules, but in this way the administration and efficiency loss that is always the effect of regulating rules can be kept at a minimum.

It could be beneficial for our understanding of the market as a self-organizing system to extend Adam Smith’s metaphor to include two invisible hands: one that bakes the cake and one that divides it. The first invisible hand takes care of the non-zero-sum game of creating wealth, trying to bake as big and nice a cake as possible. With respect to this invisible hand we are all more or less on the same side, all wanting a big, nice cake out of the oven of the market. But when it comes to the operation of the second hand, we all tend to want a bigger piece of the cake for ourselves. It is important to always keep in mind that the market’s self-organising process constantly performs both of these functions, and that the outcome of each of them—the cake in the oven and the piece you get—is dependent on the constitutive rules of the market.

This means that, when we design the constitutive rules of the market, we need to take into account how such rules influence both the processes of production and distribution. For example, when we set the rules governing the length of patents and copyrights, we have to take into account that the length of the property right will influence both the efficiency of the market and the distribution of wealth. If we have no copyrights, the market will provide much less incentive for creative production. If, on the other hand, we have too far extended copyrights, this will limit the possibilities for reusing ideas for new productions that would benefit everyone. For example, and given the short-term view of the market, I would estimate that around 10 years might be an optimal trade-off. From the economic perspective of an individual copyright owner wanting a bigger piece, the longer is of course better. No wonder big copyright holders are lobbying lawmakers to increase copyrights to 150 years. Copyrights are a good example of constitutive rules; they would not exist without legislation. On the one hand, one needs to shape the rules to encourage investment, which is the main purpose of intellectual property. On the other hand, one needs to shape the rules in such a way that diversity and competition are also possible and that the overall needs of society are most fairly and effectively addressed, and therefore limit the length of property rights.

We all need to ask some simple questions, when it comes to handing over any important task to the invisible hands of the market:

- Will the market really be able to bake this particular cake? Are we using the market in the right way? Is the task structured in such a way that a meaningful (efficient, just) self-organisation will occur in the economic system? Might this be a collective good or a merit good that the market is unable to handle? Will the market work effectively in this case, or do we need to use a different tool?

- Will the cake look and taste good when it comes out of the oven? What other human values—in addition to economic efficiency—do we want to achieve in this matter? How do we make sure these values emerge as a result? How can we formulate the task and construct the constitutive rules around this problem so that the result of the market’s self-organisation is in line with the services or products we want it to provide?

- Given these rules, how will the market share the cake? What will be the distribution effects of these rules? Who will be the winners and who the losers? Can we design the constitutive rules otherwise to make the division of the cake more in line with what we would find reasonable and desirable?

“When we begin to understand social reality better, strangely, we nd that it cannot be understood without understanding ourselves as its historical co-creators."

And is it now the time to change the already existing constitutive rules? Because we now need rather different rules to shape our free market. Perhaps, in particular, we need to:

- Continue to create new ways of measuring results, a bottom line that extends beyond the purely financial. It will change the emphasis of business laws on protecting capital and investments and make their duties broader.

- Provide shareholders with wider responsibilities. We need to re-impose obligations on shareholders and broaden the obligations on board members and directors beyond shareholder interests.

- Limit companies’ status of personhood. Businesses still need to be individual legal entities, but to give them human rights and freedom when they have overwhelmingly more power than most people jeopardises democracy.

- Promote a long-term view on business. Short-termism is a persistent problem for public limited liability companies. Perhaps if you commit to owning shares for ten years you ought to get ten times the voting rights.

- Democratise decision-making in business. Perhaps forms of participatory democracy can be incorporated so that employees have efficient ways of making their voices heard in the overall development of the company. This could be supported and facilitated by new legal forms of corporations.

When we realize that the way the market self-organizes is always a function of not only individual consumer decisions but collective political decisions about the constitutive rules as well, we will no longer be able to hide behind the concept of a “free” market. We humans need to take responsibility for the outcome of the market. In order to do so, we need some kind of a reference frame to judge the market from. We need a reference frame greater than the market, a meta-narrative greater than the market. The problem is that we now have the correct post-modern insight that all meta-narratives are also man-made. This forces us to focus on the political process of formulating a new meta-narrative.

9. Need for a new ‘meta-narrative’

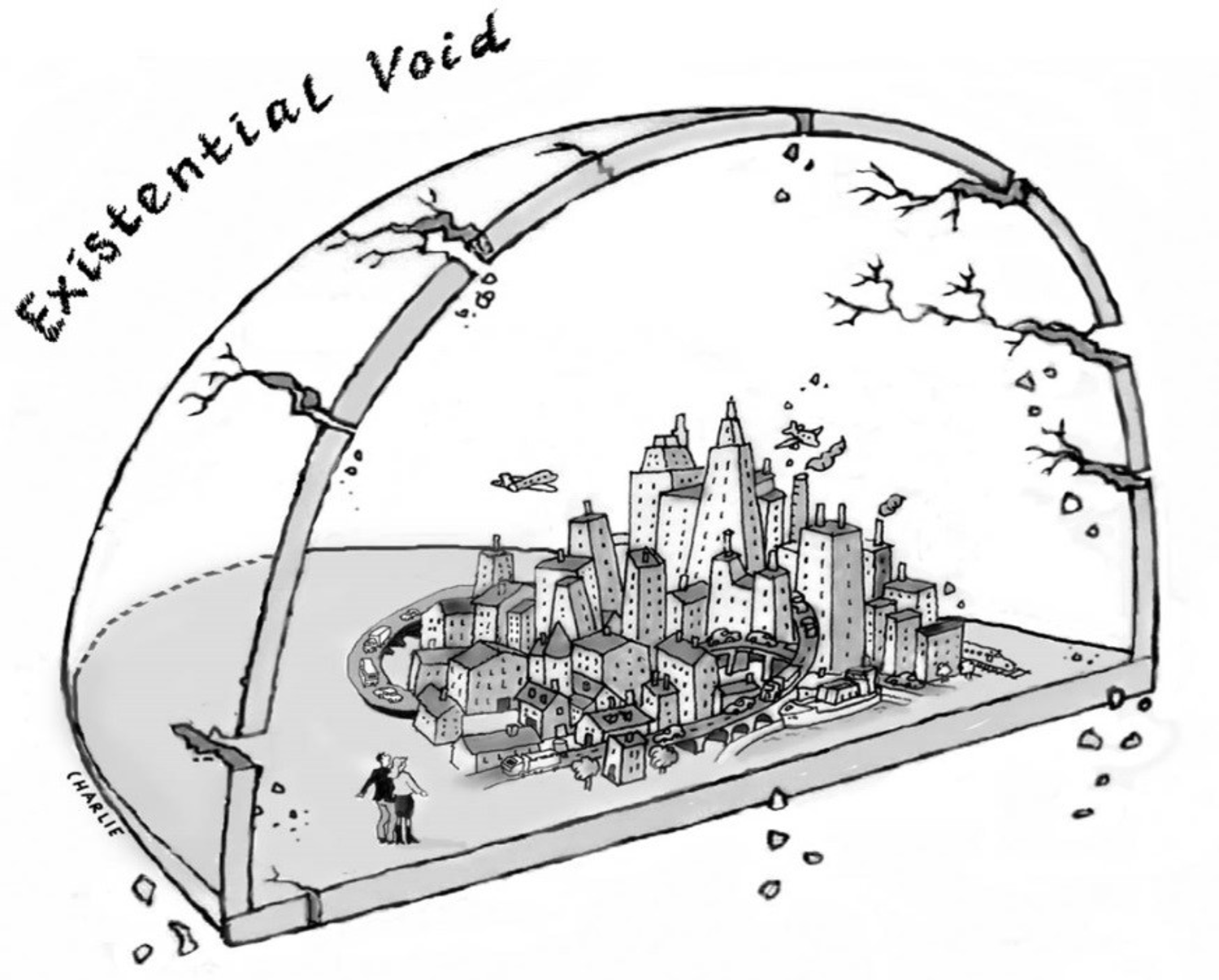

My fear for our society is not so much the various external threats we face, but rather the kind of emptiness and meaninglessness that can destroy society from the inside.

I believe that humanity has moved from not being at all aware of economics and the market, to understanding the market as a system of its own in the classical model. And that we are only now discovering how the economic reality we have taken for granted was really a mirror image all along, a reflection of our own inner lives, our hopes, fears, ideas and desires. When we begin to understand social reality better, strangely, we find that it cannot be understood without understanding ourselves as its historical co-creators.

Back in 1945, philosopher Karl Popper described the difficulty the market has—not in achieving efficiency—but in generating significance, meaning and value systems. His master work The Open Society and Its Enemies, warned us against this lack of meaning as well as against the classic totalitarian forms of control. In earlier societies, it was the lack of food and material goods that was the biggest problem; the richest societies now instead faced a lack of meaning and purpose, he said.11 Market logic has relegated the role of citizens to passive consumers.

This is even true at the political level, where citizens are expected to push the political ‘shopping trolley’ between producers of political goods. When it comes to religion, they are reduced to choosing an individual product aimed at their personal needs. Even our love lives are reduced to a commodity where potential partners are considered as products to be kept or dumped, and who rarely live up to the marketing promises of magazines and media.

The market system needs no sense of meaning to work, but both society and individuals do need a symbolic system to create meaning. We need to operate within a context to know that we are part of something meaningful, something greater than ourselves that frames our lives and provides language and reference points to understand and navigate it. Without a larger frame, society unravels into a collection of individuals who are mere economic entities in the market. A society cannot consist of consumers and producers only, yet this is the vision of our world promoted under the current market-liberal worldview.

"How do we balance our needs today with the needs of future generations?"

As discussed earlier, one definition of myth is this larger frame: the ultimate justifier and ultimate authority in a society. This kind of myth provides the meta-narrative—the big story—that keeps our society together in what may be an arbitrary, but also a necessary way. The American sociologist Peter Berger calls it “sacred” because there is nothing beyond it that can help us value it.12 The myth is untouchable and beyond our judgements. It ‘just is’. It shields us from the fact that we have to provide our own ultimate authority on which to build our otherwise completely arbitrary society. Like a “sacred canopy” it shields us from our collective existential void: it hides the fact that it is all up to us to create the symbolic system in which human values, meaning and purpose can be formed. This symbolic system and its meta-narrative are per definition a shared collective good, which, like all other collective goods, the market cannot produce.

Every society, every culture, has got its own outer boundary: its meta-narrative. For our emerging global society it is the Market. After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, there was just this one contestant for a global meta-narrative remaining. The market claimed to be the ultimate “sacred canopy”. This was the “end of history”.13 This would suggest that we have abandoned our search for collective meaning, replacing it by a pursuit of individual utility. In practice, the Market serves the same purpose as God or Science once did: to provide us with an external ultimate authority. We have reverted to living under false absolutes, rather than living authentically, as the existentialist philosophers urged us to do. We believe that somehow, and uniquely, the market ‘just is’. We are, in short, still alienated from our systemic freedom: the freedom we can only exercise collectively in order to change the internal workings of our socially constructed systems.

The market has evolved as the unreflective answer to our need for collective coordination in today’s world and our need for an ultimate authority. As an ultimate authority the Market myth is very thin. As efficient as the market is for allocating private goods, it is that poor at providing a satisfying shield against our collective existential void. And many can now feel the cracks in this shield. It must address the important common question of efficiency, and must also address questions about other common human values like justice, equity and meaning. Collective questions like ‘How do we balance our needs today with the needs of future generations?’ require a bigger framework to be answered.

Hayek and his friends at Mont Pèlerin in 1947 were myth-makers in both senses of the word. They were busy re-writing the story for our times and, as we have seen, this was propagated to the world as more than just economic doctrine. But at least that shows that it is possible for humanity to grasp the myths that govern the world and to rewrite them. Hayek and his colleagues did it. We need to do the same.

So far in history we have handled this by pretending that this collective systemic freedom does not exist. We have deferred our decisions to an external “ultimate authority” of different kinds in different societies and different points in history: God, Science or the Market—at each step increasing the complexity of our meta-narrative to meet the increasing complexity of our world. And now we need to do this again. We need a means by which we can agree on the common good that is the ultimate purpose of the economy. What do we want “the two hidden hands” of the self-organizing market to deliver? How do we define the common good? How do we define equity and justice? How do we balance our needs today with the needs of future generations?

And, again, the important insight is that these collective human values—as opposed to individual values like beauty—cannot pertain to the individual and her preferences alone. Ethical values must per definition have a collective aspect as they refer to the relations between individuals. Justice and meaning do not exist outside our common social reality. They are created in the relationships between individuals, not within single individuals. They are integral parts of our socially constructed world that we share with other people.

The world has become too complex and too fast moving for us to be able to formulate utopian visions of the future. We cannot any longer say what we want the world to look like in fifty years. But our inability to formulate precise visions must not stop us from taking responsibility for framing the future. However, the focus needs to shift from having a vision of the good outcome of history to having a focus on what a good process might look like. In our democratic market-society, “politics” and “the market” are the two most important processes that constantly form the future. We need to look closely at the constitutive rules of both these processes. Good rules for the political process are a prerequisite for creating good rules for the market. Our new narrative will have to be a narrative about the good man-made processes rather than utopian end results of the historical process.

10. Conclusion

"How do we build a new meta-narrative when we have so many different, irreconcilable perspectives?"

First insight: We as humanity hold a systemic freedom to shape the inner workings of the market as a self-organizing system. A freedom we can only exercise collectively.

Second insight: We are in dire need of a bigger common framework than that of the Market, in order to be able to use our systemic freedom to create our social reality; not only for efficiency and individual interests, but also for the common good. We need a new meta-narrative.

The third important insight: We will never find this frame of reference, this meta-narrative, ‘out there’, as an object in the natural world, like we thought we had done with God, Science or the Market. We realise that all meta-narratives are in some way arbitrary and they are all man-made—but we still need them in order to survive and flourish, both as individuals and as humanity.

Now we have to face the fact that we can look for no other place to find this meta-narrative than amongst ourselves: in the dialogue between humans. Our biggest frame of reference is always man-made and arbitrary. This is a source of enormous collective existential angst and the reason why we mobilise all our internal defences to avoid addressing it. It feels so much better just to continue pretending that we are in the hands of an external ultimate authority.

Previous generations might have looked to religion to provide the framework of a narrative by which they could judge the market, but that is not a path that is really open to us now. This is both a problem and an opportunity. The problem is that we can’t rely on any other external authority to provide an objective meta-narrative. The opportunity is: we are free to create one.

But why one meta-narrative? In a pluralistic and multi-cultural society there is surely place for more than one narrative! Yes, and in order for those narratives to be able to co-exist and to interact in a positive, constructive way that enriches our understanding and provides multiple perspectives on our world, rather than interact in a negative, competitive and violent way, we will need a good, meta-cultural “holding environment” for these multiple cultures/narratives. That meta-cultural holding environment will also have to be part of the new meta-narrative.

This brings us back to the main problem: how can this new global meta-narrative and meta-cultural container be formulated, especially when we have no means of agreeing on anything globally, and when the prevailing post-modern world view is suspicious of collective ideas of all kinds? So how do we build a new meta-narrative when we have so many different, irreconcilable perspectives?

We will never reach a final form of this narrative. It will have to be an open-ended process, and the narrative will be about this process. Still, it is within our powers to create a good narrative forming process with rules that continually challenge the narrative and keep the dialogue alive. It is, in that respect, the most important project in human history: it began many millennia ago, but it has also only just begun. As complexity in our society increases, every so often this process gets stuck in a cul-de-sac—as it has done recently—and needs to be kick-started again.

Notes

- Ha-Joon Chang, “23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism,” The Royal Society of Arts http://www.thersa.org/events/audio-and-pastevents/2010/23-things-they-dont-tellyou-about-capitalism (quote at around 27 minutes)

- Adam Smith, Lectures on Rhetoric and Belles Lettres (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983).

- W.J. Samuels et al, Erasing the Invisible Hand: Essays on an Elusive and Misused Concept in Economics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011).

- Quoted in P. Inman, ‘Beware false sightings of Adam Smith’s Invisible Hand,’ The Guardian 7 Oct, 2011 http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2011/oct/07/economics-invisible-hand-adam-smith

- P. Mirowski, and D. Plehwe, (eds.) The Road from Mont Pelerin: The making of the neoliberal thought collective (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009), 373-4.

- Friedrich Hayek, The Road to Serfdom (London: George Routlege & Sons, 1944)

- Robert Kegan, The Evolving Self: Problem and Process in Human Development (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1982).

- Tomas Björkman, The Market Myth, In press

- Fritjof Capra and P. L. Luisi, The Systems View of Life: A Unifying Vision (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014).

- John Searle, The Construction of Social Reality (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995).

- Karl Popper, The Open Society and its Enemies (Routledge, London, 1945).

- Peter Berger, The Sacred Canopy (New York: Doubleday, 1967)

- Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992).

- Login to post comments