Hello Visitor! Log In

Human Security: Its Pasts, Its Underway Evolution and a Necessary Future

ARTICLE | August 1, 2023 | BY David Harries, Lorenzo Rodríguez

Author(s)

David Harries

Lorenzo Rodríguez

Abstract

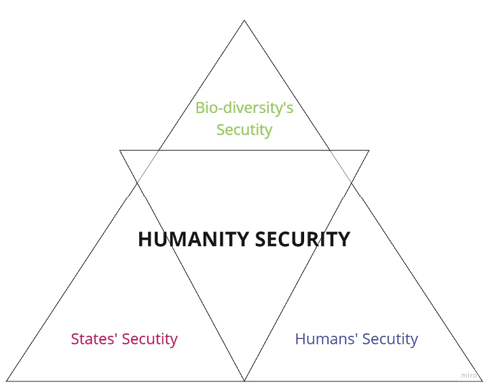

Human Security has had a checkered history since its formal announcement in the 1994 UNDP HDR. This paper argues that current circumstances should be exploited to recontextualize security to better acknowledge planetary realities. Humans’ security is only one of three fields of planetary security and needs to be considered in concert with the other two; states’ security and biodiversity security, if it is to receive sustained and durable attention. A brief overview of the history of the Human Security field briefly notes its two high points; HS1 in the late 1990s and early 2000s, and HS2 following the 2013 UNGA announcement of the Human Security First campaign. Some of the reasons for the failure to gain traction for more than a small community of activists are described for each. The core of the paper explains why the concept of Humanity Security deserves to be the concept underpinning consideration of security of all the planet’s citizens, of their states and communities, and of all life in the air, on land and underwater, especially now. Pragmatic suggestions for achieving the reconceptualization of security in doable and useful ways are offered. The focus is on three considered deserving of priority. One is the universal deployment of strategic foresight for all policy-design activity to enable better preparation for an uncertain future with fewer surprises. A second is the establishment of a new UN USG to provide leadership and impose oversight of action on the 17 SDGs, currently all behind schedule. Third a 21st century version of ‘security sector reform’ is overdue, based on a protocol of enlightened interoperability that enables harmonious relationships among diverse communities of security and non-security actors. The paper concludes with advice from the Russell-Einstein Manifesto: “Remember your humanity and forget the rest.”

Security has a very long history. The planet’s flora and fauna, centuries before the evolution of homo sapiens, co-existed in a complex system of interdependent security. The flora provided food and shelter for the fauna, which returned the favor as oxygen and nourishment for the flora throughout life and death. Human Security was first implied by the earliest humans gathering flora and hunting fauna to provide for their families. Their gathering and hunting tools improved through the stone and iron ages, promoting the assembly of families in communities that today might be considered cooperatives.

As communities grew into villages, towns, and cities—the largest of which became the earliest states—competition developed, and conflicts broke out over access to and availability of flora and fauna needed for growing population, i.e., to be required for the security of the states’ citizens. Human nature guaranteed that this early ‘state security’ would evolve into a competitive ecosystem of production (commerce), protection (weaponry) and power (political leadership) in each of what, until modern times, was a globally scattered patchwork of states’ security complexes—the distances between them allowing for few deliberate connections.

The industrial age of steam, electricity and telegraph ushered in factory-enabled mass production, global empires, and more concentration of population able to reach out to others, for good and bad. The security of the individual in nation-states surrendered precedence to the state’s security. The production for, protection of and accumulated power and prestige of states has enabled and underpinned centuries of conflicts over control of homeland and empire, and the land and sea-lanes among them, flora and fauna both natural and farmed, religion, natural resources such as gold and silver, and the human beings to man industry, extraction and the military. Nevertheless, through the centuries, every human being has continued to consider their safety and well-being of paramount importance, as, admittedly unevenly, do today’s nearly eight billion planetary citizens. The debate—not infrequently the argument—over which of human and or national security deserves priority is guaranteed in the long run.

1. Security in Modern Times

Definitions and descriptions of security abound, depending on whether the focus is its condition, or who or what is being secured. For the former, it can be most briefly expressed as how confident can people be, and do what they want in the absence of fear and desire. More comprehensively, security recently has become everybody’s business, everywhere. With the fading of once-clear and firm boundaries between military and civilian communities, public and private sectors, private profits and public well-being, combatant and non-combatant individuals, and even between war and peace, for better or worse, everyone became not only a security stakeholder but ever more explicitly, a security participant. The trend continues and arguably is strengthening as a global polycrisis expressed on some symptoms such as increased pandemic outbreak risks, democratic backsliding, rising inequality, weaponization of food and health and energy, internal displacement, refugees and migration emergencies, cyberwarfare, absence of rigorous accountability and climate change, threatening the well-being of more and more people and places with less and less likelihood of meaningful progress on—let alone solution of any one element and certainly on the crowded ‘map’ of their interconnections.

Overall, the beginning of this landscape shift can be attributed to the end of the Cold War. Once the strategic dilemma between the superpowers ended, several changes in the International Community took place. For instance, the progressive democratization of the former Soviet Republic. The competition for the most considerable influence in the Global South also opened space for a new set of questions regarding the formerly ignored “low politics” of culture, health, technology and economic affairs. At the same time, in Europe, four theoretical perspectives started to rethink the concept of security but, most importantly, the object of study. This group of Critical Security Studies* is the following:

- The Copenhagen School focused on securitization.

- The Paris School focused on insecuritization.

- The Aberystwyth School focused on emancipation.

- The Human Security School focused on humanization.

In some way still related with the National Security approach, the continental schools maintain their theoretical perspective centered in the State level of action, focusing attention on the behavior and policy decisions representing non-military aspects of security from a constructivist standpoint. However, the Welsh School as the Human Security School, is inclined to an individual level of security, though the latter does it with a looser body of literature and without a rigid intellectual tradition guiding its research. Crucial for the handling of the polycrisis, is this shift to an individual scope in which the human being and not the State is the starting point for the decisions to guarantee security.

But, the policy field of Human Security in modern times has had only sporadic success. And until the many security consequences of the intensifying polycrisis are much more strongly acknowledged, collectively and collaboratively, its future as a global mainstream issue driving geopolitical action will be no better. On 22nd July 1974, the second full day of the Turkish invasion of Cyprus, the Special Representative of the Secretary-General of the United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus (UNFICYP) used the term in a statement of concern for citizens of Greek and Turkish villages in regions controlled by forces of the other side. Another 20 years passed before its establishment in the 1994 United Nations Development Program’s Human Development Report. And since then, Human Security (HS) never became more than a complimentary issue, even during the two periods when it received significant attention. These we are titling Human Security 1 (HS1) and Human Security 2 (HS2).

HS1, during the late 1990s and early 2000s, had its high point in the period of the publication of freedom from fear, Canada’s foreign policy for human security, which demonstrated the country’s intention to focus on the ‘people’ side of security,† the Human Security Report 2005,‡ and Human Security and International Insecurity, and massively detailed and provocative telling of the influence of human security on international security in the broadest sense.§ Many members of the Middle Powers Initiative¶ were attentive during this time but to little avail, as HS remained ‘on the margins’ until being thoroughly sidelined by the 2008/2009 Great Recession. Throughout HS1, human security was in a political and intellectual ‘competition’ among national or state security and human well-being proponents. Each side had very different goals and priorities, and there were few attempts to reconcile them. One effort was done by Walter Dorn,** who produced a three-part framework for their consideration.

The first element was a list of the Priorities and Initiatives for each type:

|

Human Security |

National Security |

|

Priorities & Initiatives

|

Priorities & Initiatives

|

As seen in Table 1, these competing set of primary considerations open a wide range of application areas that could seem mutually exclusive. Nonetheless, before the latest 2022 Special Report on Human Security: New Threats to Human Security in the Anthropocene demand advocacy for solidary, Dorn’s†† efforts to frame a “Common Security for a Common Humanity” were guided by the idea that security has an overlapping nature in which commonalities and externalities among groups need to be recognized. This exchange of perspectives, goods, services, and ideas opens space for opportunities while also enhancing existing vulnerabilities. Contrasting their respective goals as shown in the following

Table 2 becomes necessary to understand the shortcomings and intellectual blind spots present in both approaches and why an integrated approach was necessary then as it is now.

|

Human Security |

National Security |

|

Goal: Protection of human beings everywhere |

Goal: Protection of the home state and its citizens |

|

Favored by liberal internationalists, who stress that:

|

Favored by the real politique school, who stress that:

|

Lastly, the third element of the Framework proposed that ‘organized human security’ and enlightened national security are “one and the same.”

Unfortunately, Dorn’s effort was not followed up. Furthermore, exponents like Roland Paris‡‡ or Barry Buzan§§ strongly signaled that the overreaching concept of Human Security had no academic or policy use. At the same time, Ken Booth from the emancipation paradigm pointed out its instrumentality for States in the realm of rhetoric.¶¶ Even within its supporters, Human Security finds a strong opposition between the proponents of the narrow versus broad definitions of the approach. For instance, the narrow definition supported by Nicholas Thomas and William Tow focuses on freedom from fear through conflict prevention and resolution. In contrast, the broad definition leveraged by Martha Nussbaum, Amartya Sen and Caroline Thomas emphasizes freedom from fear and freedom from want by advocating for more general social issues such as health and education.***

|

Organized Human Security |

Enlightened National Security |

|

|

More telling, it is argued, is that not one of several major international initiatives at the time, all on ‘security’ and well-being, even mentioned the term human security. Not any of the eight Millennium Development Goals, not the Responsibility to Protect (R2P), not the ten Principles of Global Compact, not John Ruggie’s UN Framework for Business and Human Rights—Protect, Respect, Remedy one of the earliest of the now many triple bottom lines, and nowhere found in the voluminous writings on the ‘peace dividend’ that so many believed was “surely imminent” after the end of the Cold War.†††

Human Security 2 was provoked in December 2013 when the “Human Security First” campaign was launched, as undertaken by the Global Partnership for the Prevention of Armed Conflict (GPPAC), a network of civil society organizations which actively promotes a more comprehensive approach to conflict prevention. It is a platform for gathering local perspectives on the added value of human security and its importance to the post-2015 development agenda. From the perspective of these non-governmental organizations, there can be no development without human security. However, the campaign did not gain traction.

And then, not one of the 17 SDGs announced in 2015 discussed ‘security’ or employed the term Human Security. The 2016 election of Donald Trump reinforced the underway decline in democracy worldwide, as documented by organizations like Freedom House‡‡‡. Through the use of expenses of a nationalistic rhetoric the type and degree of multinational collaboration that would be needed even to keep Human Security on the radar are obstructed. Increased

anti-globalist narrative and isolationist policy decisions are potent barriers to Human Security.

"Humanity Security must intellectually underpin all action for all aspects of security."

Moreover, another ‘competitor’ for Human Security is earning the status of a ‘security’ in crisis: biodiversity security. Its two ‘pieces’ are both causes and effects of the consequences of climate change. One is the loss and even extinction of whole species of living things. The other is the reduction of both the space on earth and the health of the oceans that planetary citizens and their biodiversity need to survive well to be able to live, move and work safely, satisfyingly, and sustainably.§§§ Failing to protect all species is a planetary injustice, in addition to being potentially lethal. In research from Muluneh¶¶¶ climate change has “the potential to reduce species that are unable to track the climate to which they are currently adapted and resulted in extinction risk.” Hence, it is not a surprise when supplementing research affirms that “biodiversity loss will likely decrease ecosystem functioning and nature’s contributions to people.”****

Given the global patchwork history of human security, it seems worthwhile to try to rebrand the concept to recognize how significantly its context has changed so that more people are attracted to collaboratively address problems that threaten their collective wellbeing with sustained tangible and durable action. Current events, circumstances and conditions provide enough evidence of the validity of this claim. Some statistics will help contextualize the necessity of the perspective change. According to the United Nations Development Program,†††† since 2002, the world has lost more than 60 million hectares of tropical forest in the Congo and Amazon basins; across 109 countries, 1 billion people representing 21.7% of the total population, live in multidimensional acute poverty. Moreover, by 2030, the expected trend is that 900 million people could be undernourished due to food scarcity. About violent conflict, numbers are no less worrying. Only in 2020 did the number of forcibly displaced people reach 82.4 million. In particular, the Uppsala Conflict Data Program‡‡‡‡ indicates a toll of 120.648 deaths in 2021 regarding State-Based Violence, Non-State Violence and One-Sided Violence.

Again, arguably, the polycrisis is a mutually reinforcing dynamic of a cause and effect of the end of most of the significant assumptions leaders and their international communities have depended upon for decades to guide their planning, policy development and implementation. It is not an overstatement to claim the globe is woefully ill-equipped for change, even change that can be forecast and predicted, let alone all the future holds that cannot be prepared for with confidence because it is more than hours or days ahead. Indeed, until humanity can improve its ability to imagine what might be ahead, its capacity, in the event, can only be reactive, with too little of the proactivity that will be demanded.

2. The Way Ahead – HS.3

It is time—a necessity—to design, structure and resource a durable HS3. The authors proposed that Human Security must be renamed Humanity Security. This recognizes the reality that security needs to be more than just of and for ‘humans’, but of and for all planetary life as pointed out in the 2022 Human Development Report published by the United Nations Development Program on February. Humanity Security must intellectually underpin all action for all aspects of security.

As generic guidance, it is suggested that Einstein be remembered on two fronts; one for his definition of insanity and the other for his contribution to what, at the time, was a major statement on human security. He defined insanity as continuing to do the same thing again and again while expecting different results. And the Russell-Einstein Manifesto he penned with Bertrand Russell that addressed the threat of nuclear war concludes with “Remember your humanity; forget the rest”.§§§§ Better, in 2022 and beyond: Remember your humanity; there is nothing else.

Several actions are needed now that are imminently doable, not costly, very unlikely to upset even the most committed selfish autocrat and, individually and collectively, offer civil society many opportunities to participate and invest in substantive work. This can improve the likelihood that their future and that of their children will enjoy a future measurably better than that towards which humanity is heading today.

- Deploy Strategic Foresight. It is the capacity to anticipate and act in the present to meet one’s needs in the future. Absent the regular, if not continuous, the exercise of this discipline; it is inevitable that any action for Humanity Security will remain ‘reactive’. Given the accelerating pace of unpredictable change and its consequences, being reactive is less and less ‘fit-for purpose’ and may even be dangerous. Work on Humanity Security needs to be proactive enough to produce outcomes that 1) offer more of what even today’s dismal conditions demand, 2) are far more relevant to the demands of the future, which, as early as tomorrow, is unpredictably uncertain, but will not be a repeat of today. There can be no experts on the future, but everyone needs to be more aware of what the future might hold, hopefully in time for it not to contain destructive shocks for which humanity is unprepared. In this regard, this willingness to act towards the future may mean letting go of structures, policies, tactics, or programs—or even the organization’s mission—that may have once been effective but may leave the organization stuck and increasingly becoming obsolete in the long run.

- Establish an Under-Secretary-General for Human Security at UNHQ in New York. This would be a small step on the journey toward the structural and procedural reforms urgently needed at the seven decades old UN. The UN’s Human Security approach needs much more effective, efficient, and coherent planning. In order to make it happen, a committed representative at the highest level of UNHQ to harmonize the current actions and projects is needed.

- Establish Interoperability as the protocol guiding collaboration rather than integration. The ‘silos’ of organizations and institutions will not disappear for all the wasteful fragmentation they are known to cause. And many of the silos have good characteristics it would be unfortunate to lose. But ‘integration’ would promote that loss by dumbing down the best, giving free rides to the worst, and making it nearly impossible to assign and achieve real accountability in an ‘integrated’ community where no one leads. Calls for homogenization fly in the face of the almost universal claim—however variably expressed—that there is unity in diversity. But ‘Silos’ do need a re-set; renovation of operating procedures so that occupants are enabled and encouraged to see, hear, speak and share knowledge and intentions with those in other silos. Opening information silos and removing communication and cooperation barriers that create unnecessary divisions between “islands in the sea of knowledge”. Softening competitive tensions between organizations and creating thematic connections between disconnected actors.

- Think Leadingship. Experts and bosses, however knowledgeable, experienced or revered, must not be allowed to continue to ‘monopolize’ ‘leading’; how it is done and its outcomes. Ignoring the potential contributions of ‘followers’ and the youth of today who will become tomorrow’s doers—as leaders and followers—is not only the height of unnecessary willful blindness but a recipe for ever more intergenerational protest and unrest.

3. Conclusion

Across the world and over time, security concerns have occupied a key place in the hierarchy of human activity. Historically, those security concerns have been focused on internecine and/or domestic sociopolitical conflicts and conditions between or within societies and nation states. However, there is an increasing acknowledgement¶¶¶¶ that both national and human security depend on the viability of the biosphere. Humanity must operate on these three approaches—State, Human and Biodiversity Security—as one in order to be sufficiently able to shape the context for each in ways that provide the insights for a saner management of our societies and resources. A clear acknowledgment of the planet’s polycrisis is needed, which is a convergence of mutually reinforcing problems. For instance, conflict zones across all world regions, a continuing risk of epidemic and pandemic outbreaks, along with more frequent and extreme weather events. When nations and subnational groups are expanding their arsenals and fighting wars within and between porous national borders, it is difficult to make progress towards a shift between traditional military approaches to security and the Human Security school of thought.

Nevertheless, the change is urgently needed. There is no way for the people and countries of the globe to be safe without also having an adequate environment capable of sustaining their needs; according to Isbell et al.’s research, “experts estimated that the global threatening or extinction of species reduces ecosystem functioning and NCP by roughly 10-70%.”***** Recently, these intersections on risks have taken on an increasingly critical role. Human Security has become more comprehensive in its definitions, and the inextricable links that connect it with Biodiversity Security and State Security are becoming clearer. In this regard, local and international organizations exert an influence on society that correlates with the successes and failures of this system of systems.

The security-biodiversity nexus generates various dynamics that can increase pressures over the rule of law and undermine democracy. These forces are driven by the interplay between the two concepts. For instance, it can exacerbate existing inequalities and stirs up conflict both inside governments and countries and between them. Only a small fraction of the world‘s population has the resources and capabilities necessary to maintain their resilience in the face of adversity. Hundreds of millions of people who are living in poverty are the ones who will feel the effects of state insecurity and the harsh repercussions of biodiversity insecurity the quickest, most profoundly, and the longest. Agendas for this, most notably the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals and the Declaration of the 21st Conference of the Parties (COP), tacitly and openly stress security and biodiversity’s overlaps and linkages with one another. But it is not enough. Humanity and its planet are ONE system of systems, each and all complex and dynamic and interconnected. Humanity Security for all, or Human security for none!

Bibliography

- Hampson, F. O. (2012). Human Security. In P. D. Williams (Ed.), Security Studies: An Introduction (2nd ed., pp. 279–295). Routledge.

- Canada. Department of Foreign Affairs & International Trade. (2002). Freedom from Fear, Canada’s Foreign Policy for Human Security–2nd Ed. The Department.

- Human Security Centre. (2006). Human Security Report 2005: War and Peace in the 21st Century. Oxford University Press.

- Frerks, G., & Goldewijk, B. K. (Eds.). (2006). Human security and international insecurity. Wageningen Academic Publishers.

- History & Achievements. (n.d.). Middle Powers Initiative.

- Dorn, W. (2003). HUMAN SECURITY: FOUR DEBATES [Slide show; PowerPoint Slides]. Pearson Peacekeeping Centre, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

- Paris, R. (2011). Human Security. In C. W. Hughes & Y. M. Lai (Eds.), Security Studies: A Reader (1st ed., pp. 71–80). Routledge.

- Buzan, B., & Hansen, L. (2009). The Evolution of International Security Studies (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Reveron, D. S. (2018). Human Security in a Borderless World. Taylor & Francis.

- Repucci, S., & Slipowitz, A. (2021). Democracy under siege. Freedom House.

- WWF (2022) Living Planet Report 2022 – Building a nature-positive society. Almond, R.E.A., Grooten, M., Juffe Bignoli, D. & Petersen, T. (Eds). WWF, Gland, Switzerland.

- Muluneh, M. G. (2021). Impact of climate change on biodiversity and food security: a global perspective—a review article. Agriculture & Food Security, 10(1), 1-25.

- Isbell, F., Balvanera, P., Mori, A. S., He, J. S., Bullock, J. M., Regmi, G. R., ... & Palmer, M. S. (2022). Expert perspectives on global biodiversity loss and its drivers and impacts on people. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment.

- United Nations Development Programme. (2022). 2022 Special Report on Human Security: New Threats to Human Security in the Anthropocene: Demanding Greater Solidarity. United Nations.

- UCDP - Uppsala Conflict Data Program. Retrieved From https://ucdp.uu.se

- Russell, B., & Einstein, A. (1955, July 9). Statement: The Russell-Einstein Manifesto.

- (2022, 3p). Isbell, F., Balvanera, P., Mori, A. S., He, J. S., Bullock, J. M., Regmi, G. R., ... & Palmer, M. S. (2022). Expert perspectives on global biodiversity loss and its drivers and impacts on people. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment.

* Hampson, F. O. (2012). Human Security. In P. D. Williams (Ed.), Security Studies: An Introduction (2nd ed., pp. 279–295). Routledge.

† Canada. Department of Foreign Affairs & International Trade. (2002). Freedom from Fear, Canada’s Foreign Policy for Human Security--2d Ed. The Department.

‡ Human Security Centre. (2006). Human Security Report 2005: War and Peace in the 21st Century. Oxford University Press.

§ Frerks, G., & Goldewijk, B. K. (Eds.). (2006). Human security and international insecurity. Wageningen Academic Publishers.

¶ History & Achievements. (n.d.). Middle Powers Initiative.

** Dorn, W. (2003). HUMAN SECURITY: FOUR DEBATES [Slide show; PowerPoint Slides]. Pearson Peacekeeping Centre, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

†† Ibid.

‡‡ Paris, R. (2011). Human Security. In C. W. Hughes & Y. M. Lai (Eds.), Security Studies: A Reader (1st ed., pp. 71–80). Routledge.

§§ Buzan, B., & Hansen, L. (2009). The Evolution of International Security Studies (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press.

¶¶ Ibid.

*** Ibid.

††† Reveron, D. S. (2018). Human Security in a Borderless World. Taylor & Francis.

‡‡‡ Repucci, S., & Slipowitz, A. (2021). Democracy under siege. Freedom House.

§§§ WWF (2022) Living Planet Report 2022 – Building a nature-positive society. Almond, R.E.A., Grooten, M., Juffe Bignoli, D. & Petersen, T. (Eds). WWF, Gland, Switzerland.

¶¶¶ Muluneh, M. G. (2021). Impact of climate change on biodiversity and food security: a global perspective—a review article. Agriculture & Food Security, 10(1), 1-25.

**** Isbell, F., Balvanera, P., Mori, A. S., He, J. S., Bullock, J. M., Regmi, G. R., ... & Palmer, M. S. (2022). Expert perspectives on global biodiversity loss and its drivers and impacts on people. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment.

†††† United Nations Development Programme. (2022). 2022 Special Report on Human Security: New Threats to Human Security in the Anthropocene: Demanding Greater Solidarity. United Nations.

‡‡‡‡ UCDP - Uppsala Conflict Data Program. (2004).

§§§§ Russell, B., & Einstein, A. (1955, July 9). Statement: The Russell-Einstein Manifesto.

¶¶¶¶ United Nations Development Programme. (2022). 2022 Special Report on Human Security: New Threats to Human Security in the Anthropocene: Demanding Greater Solidarity. United Nations.

***** (2022, 3p). Isbell, F., Balvanera, P., Mori, A. S., He, J. S., Bullock, J. M., Regmi, G. R., ... & Palmer, M. S. (2022). Expert perspectives on global biodiversity loss and its drivers and impacts on people. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment.